Every pilot needs to know the difference between AIRMETs and SIGMETs.

In the simplest of terms: avoid SIGMETs at all costs and think twice about flying in an AIRMET.

But there is a lot more to it than that. Let’s start with the basics:

What is an AIRMET?

AIRMET stands for “Airman’s Meteorological Information.”

AIRMETs are issued for weather that may affect aircraft safety.

They are typically issued for:

- IFR conditions

- Mountain obscuration

- Moderate Turbulence

- Icing and freezing levels

They are not as dangerous as SIGMETs, but should still be taken seriously as they highlight weather that is dangerous to all aircraft.

How often are AIRMETs issued?

AIRMETs are issued every 6 hours starting at 0245 UTC.

AIRMETS are published by the Aviation Weather Center (AWC). The AWC will terminate the AIRMET when the condition goes away, the time runs out or, if they need to, they will extend the time.

What are the three types of AIRMETs?

- AIRMET Sierra: Mountain obscuration and/or ceilings are less than 1000′ and/or 3 miles over a wide area (over 50%)

- AIRMET Tango: Moderate turbulence or sustained surface winds of 30 knots or greater

- AIRMET Zulu: Moderate icing and freezing levels.

You should think twice about flying in an AIRMET. However, do not cancel your flight automatically!

Almost every flight can work around an AIRMET by simply modifying the flight plan.

For example, during the winter months in the Pacific Northwest, it seems like the AIRMETs Sierra, Tango, and Zulu are permanent. Every time I call for the weather I will get one or all three of those AIRMETs.

I don’t worry about them, though, because I can adjust my route. I either fly up the Columbia Gorge to avoid the mountain obscuration, I fly below the clouds and thus out of the icing levels, or I stay away from the worst of the turbulence.

You can work around AIRMETs by modifying your flight plan slightly, but SIGMETs require careful planning or most likely a canceled flight.

Don’t mess around with SIGMETs!

What is a SIGMET?

SIGMETs affect the safety of all aircraft.

SIGMETs are classified as either “convective” or “non-convective.”

When pilots think of SIGMETs they often think “thunderstorm,” however SIGMETS can be issued for non-convective (non-thunderstorm) reasons:

- Severe Icing

- Severe or Extreme Turbulence

- Dust storms and/or sand storms lowering visibilities to less than three (3) miles

- Volcanic Ash

The dust storm and volcanic ash SIGMETs are significant weather because they can cripple aircraft engines.

Read this article on British Airways Flight 9. The 747 lost all four engines after flying through volcanic ash.

The “convective” SIGMETs are pretty self-explanatory. However, I want to point out this note from the AWC:

“Any convective SIGMET implies severe or greater turbulence, severe icing, and low-level wind shear.” –AWC

You will not get a separate non-convective SIGMET for turbulence and icing. It is implied with a convective SIGMET that these dangerous weather phenomena are present.

How long do SIGMETs last?

It depends.

Non-convective SIGMETs generally last for 4 hours. However, if any of the conditions (severe icing/turbulence) are due to a hurricane, they will last 6 hours.

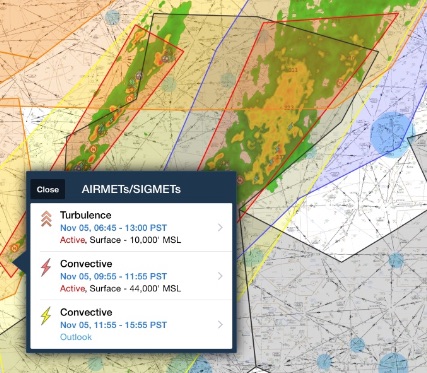

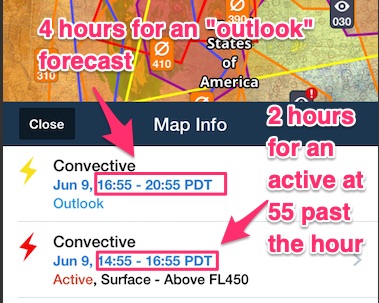

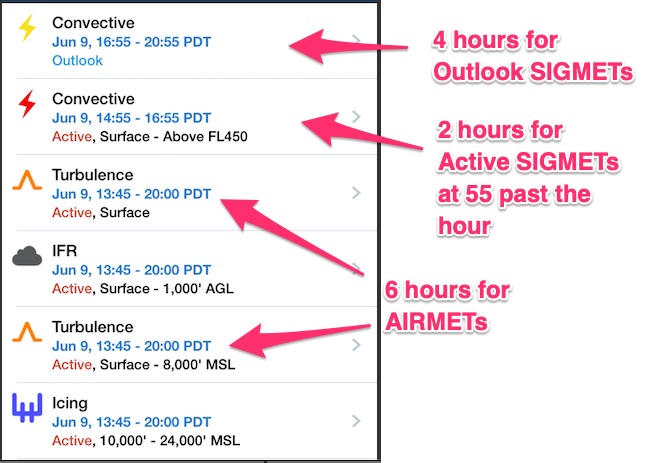

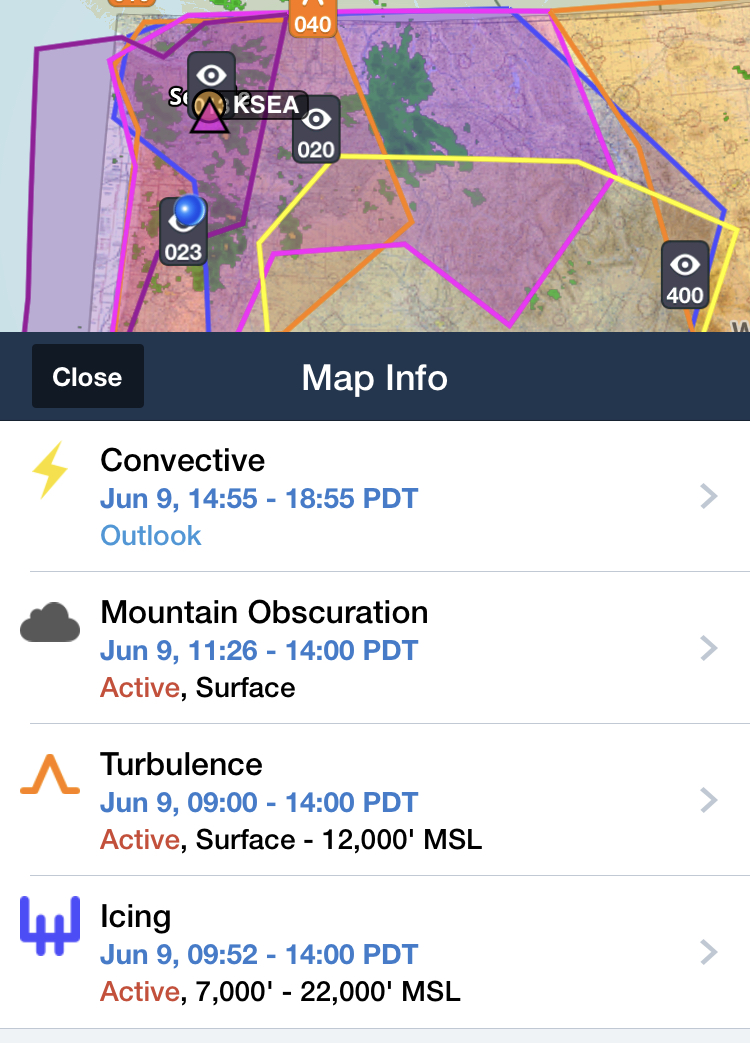

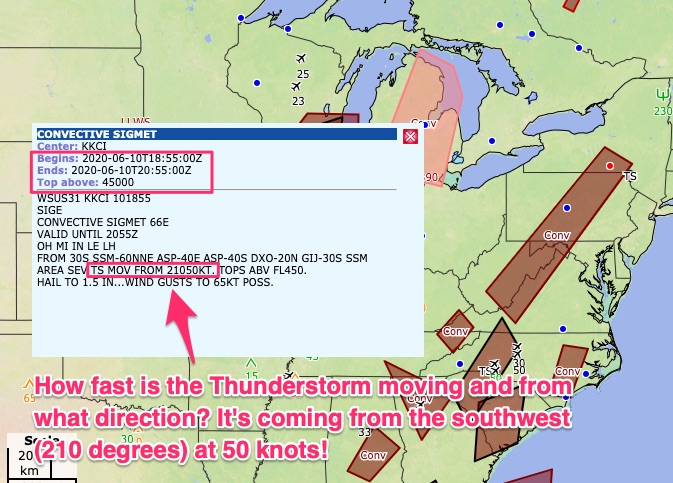

Active convective SIGMETs forecasts can be valid for up to 2 hours, but they are updated every hour, usually at 55 past the hour. Check out the times for these SIGMETs below.

“Outlook” SIGMETs are usually forecast for 4 hours.

When in doubt about how long the AIRMET or SIGMET is going to last, just look at the published time on the AIRMET or SIGMET.

Foreflight makes this really easy.

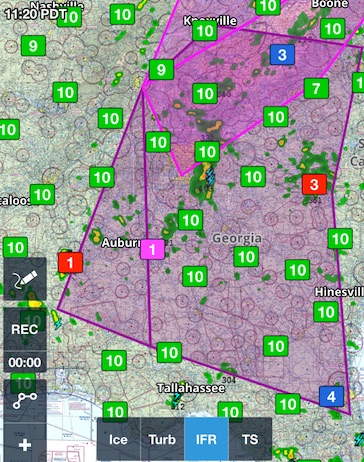

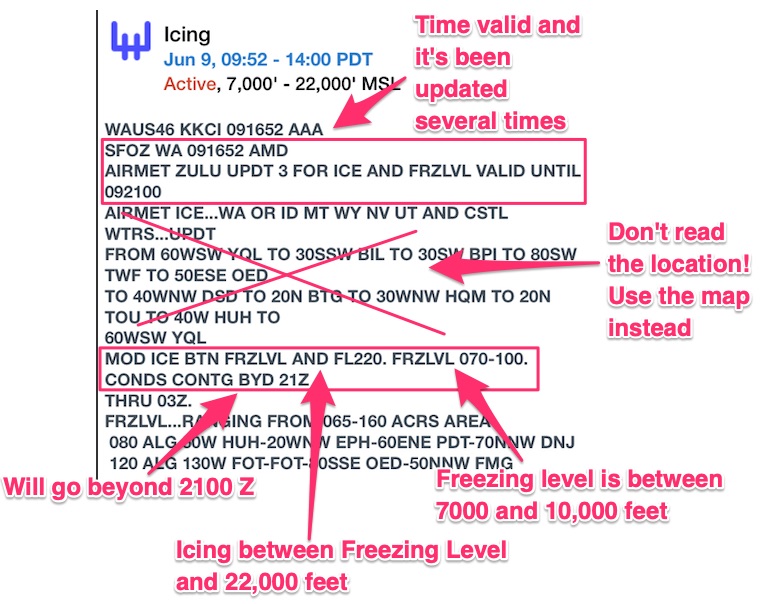

This image below is interesting because the start times for the AIRMETs don’t follow the usual 45 past the hour start times and they don’t go for 6 hours.

If an AIRMET or SIGMET has odd start times or less than 6 hours (AIRMETs), 4 hours (Outlook SIGMETs), or 2 hours (Active SIGMETs), it means have been updated.

What’s the difference between an “active” and “outlook” SIGMET?

Like AIRMETs, SIGMETs are issued for either actual or forecasted weather conditions. “Outlook” SIGMETs are just that: a prediction.

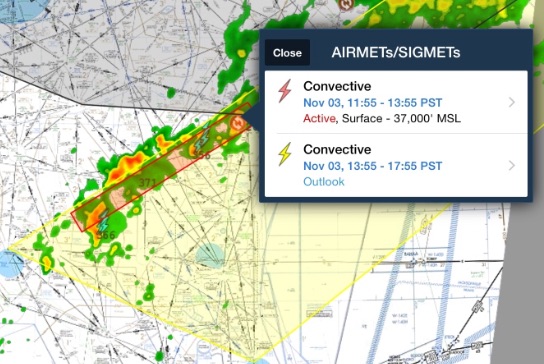

Active SIGMETs are depicted in red on most flight planning software, and they are dangerous. Outlooks are in yellow and usually cover a much wider area.

I highly recommend you adopt a “no-fly” policy in an active (red box) SIGMETs.

By making this a hard and fast rule, you completely take the decision making out of the situation. It’s already decided.

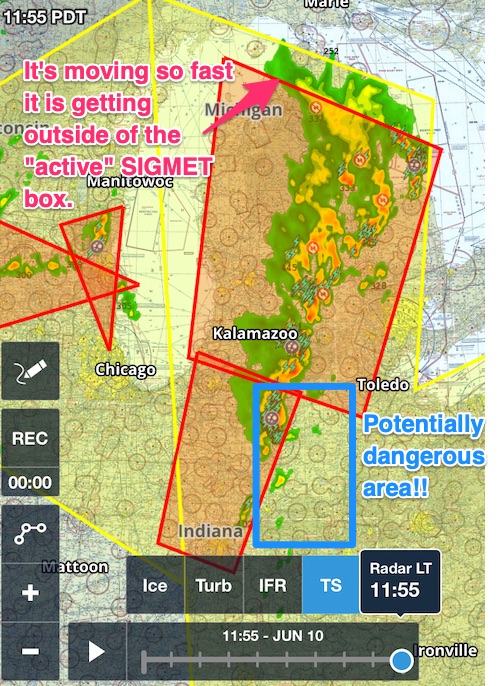

Even “outlook” areas can be dangerous with a fast-moving storm, though.

Look at the image below. The radar imagery shows severe activity outside of the red and yellow boxes.

Weather changes rapidly with SIGMETs. Don’t’ rely on the visual boxes to keep you safe. Always check the wind direction to see where the storm will be next.

Do not get lulled into a sense of security. SIGMETs of any kind should scare you.

How do you find AIRMETs and SIGMETs?

There are several ways to get AIRMETs and SIGMETs.

I prefer Foreflight. All of the pictures I’ve used so far are from Foreflight.

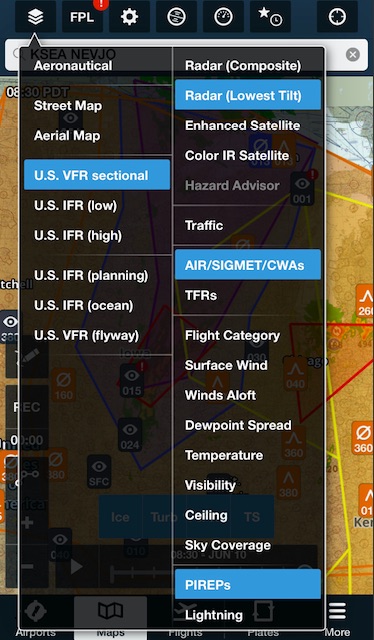

If you have Foreflight go to the map page and select “radar,” “AIRMETs/SIGMETs,” and “PIREPS.”

Then you simply tap the screen over the location you’re interested in to bring up the more detailed description.

Be sure to include PIREPs. They are vital for confirming the actual conditions in an AIRMET or SIGMET.

For more information on PIREPS, read this article: How to Read PIREPS

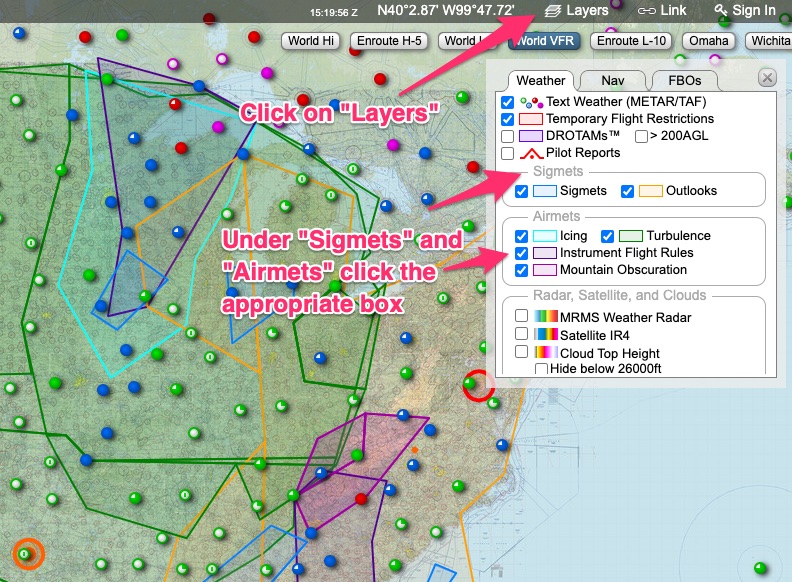

If you don’t have Foreflight, you can get them on Skyvector or through the Aviation Weather Center’s website.

Here’s how you find them on Skyvector:

Here’s how you find them at the AWC:

How do you read AIRMETs and SIGMETs?

Actually, you don’t need to “read” them. They are meant to be overlayed on a map.

The type of AIRMET and SIGMET tells you everything you need to know. Is it a mountain obscuration AIRMET? Then the mountains are obscured.

You especially don’t have to read the body of the text when you include the radar and field conditions layers and AIRMETs/SIGMETs on the same map.

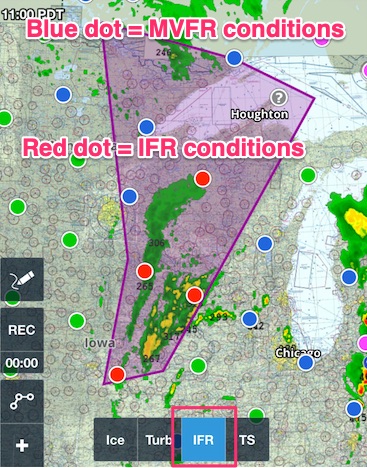

Check it out:

This is why you should always include some type of other weather overlays when looking at AIRMETs and SIGMETs. I recommend the following layers:

- Radar

- Flight Category (the colored dots)

- PIREPS (to confirm or deny the AIRMET and/or SIGMET)

- Visibility

- Ceilings

- Satellite (optional as the radar can be more helpful)

These layers can help you get a feel for the AIRMET and SIGMET. Is it accurate? Are the boundaries too large? What are pilots actually seeing? Check out this example of an AIRMET Sierra.

Remember, AIRMET Sierra’s definition is: ceilings less than 1000 feet and/or visibility less than 3 miles for more than 50% of the area.

In this AIRMET for IFR conditions, it isn’t very accurate anymore. The low ceilings (image above) and visibility (image below) only apply to a small area.

It will either expire (in this case in a couple of hours), or the AWC will drop it.

I digress, you want to know how to read AIRMETs and SIGMETs.

Most of the main body of the AIRMET and SIGMET contains a written description of the location. Therefore, you can disregard most of the body of the AIRMET/SIGMET.

The only important parts in the body of the AIRME/SIGMET are the times and descriptions of the condition (like the freezing level).

Let’s take a look at a few and I’ll show you the specific elements you should read.

The first example is for an AIRMET Zulu for Icing.

If you’re having trouble decoding the body of the text, I have a comprehensive PDF for reading abbreviated NOTAMs, METARs, and TAFs.

It will also help to decode AIRMETs, SIGMETs, and PIREPs. Click here to purchase it. I keep it up to date with unusual acronyms I run across.

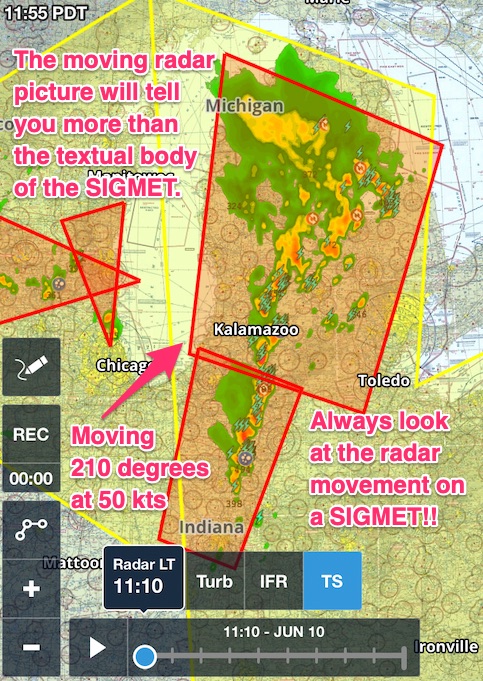

Here is another example of a convective SIGMET. I think this example illustrates best why you don’t need to read AIRMETs and SIGMETs.

Here is the same convective SIGMET on the AWC website with the full description:

The only pertinent information is the time, the tops of the thunderstorms, and the direction and speed.

But, why not just look at the radar imagery instead? Why read the description of the SIGMET?

Check out this imagery from 11:55 PDT, a full 45 minutes after the first image from above.

Yes, I could have bothered to read the SIGMET, but the moving radar shows me everything I need to know.

More importantly, the movement shows where the TS will be in the future. Notice I highlighted in blue and area outside the convective SIGMET?

Technically it’s “safe,” right? No!!!

The thunderstorm is moving into that area. Just because there is no red box, doesn’t mean it’s safe.

I will concede there are certain situations where you could fly through an active convective SIGMET.

It is an unusual situation which I covered in depth in a case study.

Read the case study: Can you fly through a Convective SIGMET?

I hope it gives you a better understanding of SIGMETs and AIRMETs.

Bottom line: SIGMETs are serious, but you can work around AIRMETs.

Hey! One more thing!

Have you been struggling with NOTAMs? Check out this FREE Ultimate Guide to Decoding NOTAMs PDF below.

You can unsubscribe after you downloaded the guide. I don’t mind, seriously.

But, you might want to stick around because I send out emails with helpful flying tips and resources.

I’m here to help!