Great question, and the short answer is yes, you absolutely can legally fly through a convective SIGMET…unless your specific operating/military regulations prohibit it.

But, the better question is: should you fly through a convective SIGMET?

I wrote an article covering everything you need to know about AIRMETs and SIGMETs. In it, I said you should NEVER fly through a convective SIGMET. I realized after a flight last week I was wrong. There are limited situations where you could fly through a convective SIGMET which I will cover here.

I am going to run through my decision making so you can see how you can safely fly through a convective SIGMET…when the conditions are right. In my experience the conditions are usually never right, but the stars aligned on this flight.

Note: this article will not discuss whether you should fly through other types of SIGMETs. You are on your own with that decision.

The Situation

I was set to takeoff around 1600 hrs from Klamath Falls, Oregon (KLMT) and fly to Portland, Oregon (KPDX).

I fly a King Air 350, so I can get well into the flight levels, which is a really important when deciding whether to tackle convective SIGMETs.

The ceilings were about 15,000 feet at Klamath. The weather at Portland looked good enough for a visual after descending through some clouds at 7,000’.

Both KLMT and KPDX were under a convective SIGMET outlook, which, you should know is a cause for a concern, but is completely manageable.

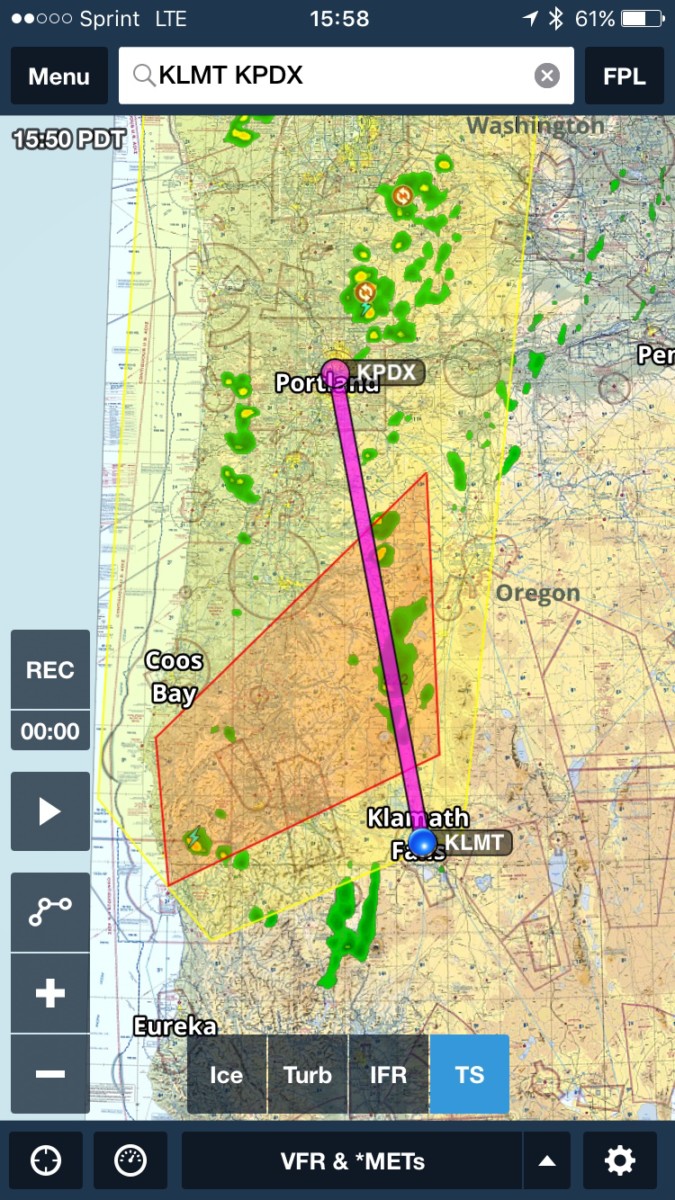

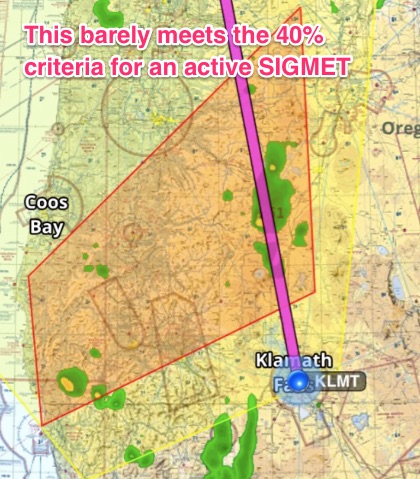

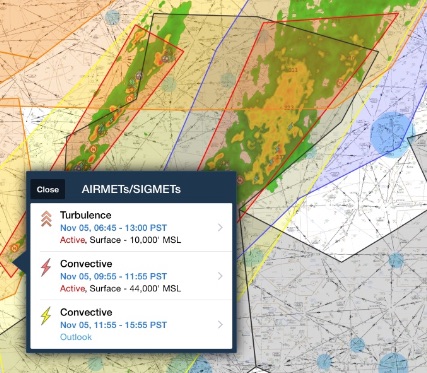

Here was what it looked like on Foreflight.

The issue, as you can see from the picture below, was not the SIGMET outlook (in yellow) but the active (red) convective SIGMET between Klamath Falls and Portland.

When I saw this on Foreflight, I thought: “OMG!!! We are never going to be able to take! We are NEVER allowed to fly through a convective SIGMET! We will NEVER get home! AAAAHHHH!”

Then I calmed down. I spent some time on Google. I couldn’t find anything prohibiting me from flying through a SIGMET, so I started thinking about what I would do. This is what I came up with:

Decision Making

Okay, so the first thing I thought of was I could adjust my flight plan to fly around it. But did I need to? The first picture you saw was just a straight line which happened to go right through a thunderstorm.

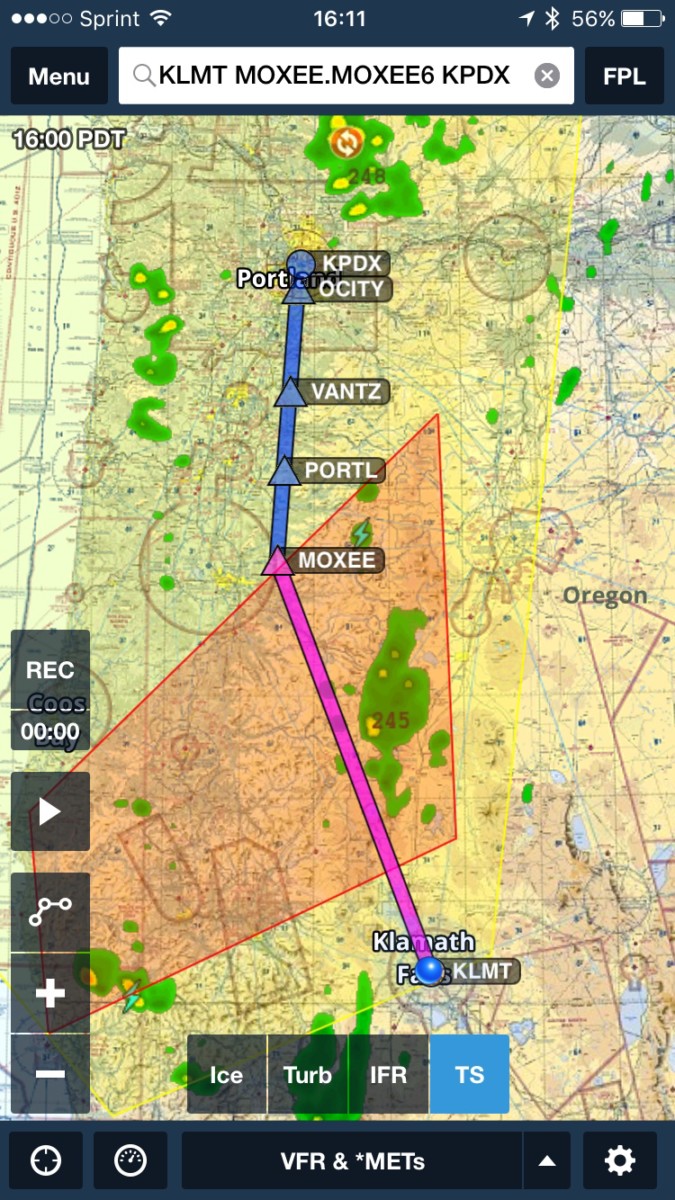

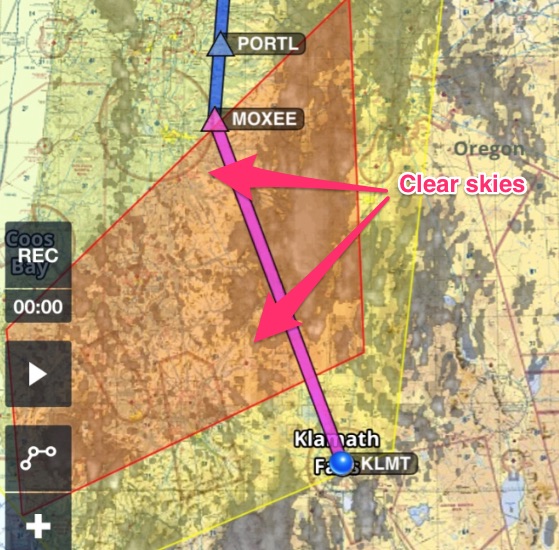

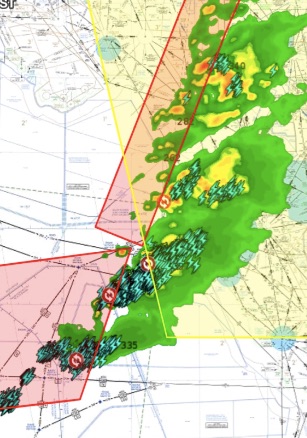

When I plugged in my actual flight plan, though, things got a little better. Check out this screen shot below.

Notice how my flight plan already took me to the left of the big thunderstorm? So, I decided not to amend my flight plan.

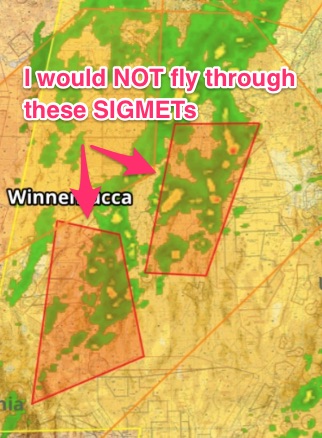

I also decided not to amend my flight plan because this convective SIGMET was a relatively tame SIGMET. Let me explain. Most SIGMETs are issued when 40% or more of the area has thunderstorm activity. Look at these two SIGMETs:

The two SIGMETs above are the kind of SIGMETs I am used to seeing. These are serious and only profoundly stupid pilots would take off and fly through these SIGMETs. You are better off staying at home or completely diverting at least 20 NM around it.

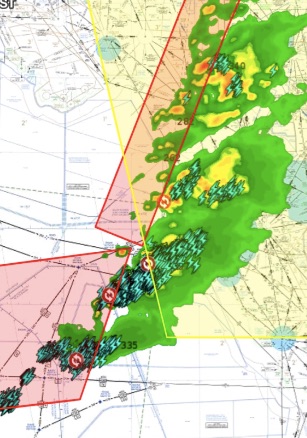

Teaching Tangent: Notice how the SIGMET sometimes doesn’t encompass all of the bad weather? Here is an example of an extreme case where the active SIGMETs are very poorly drawn. I think the weather was moving too fast for the forecasters:

Outlook SIGMETs can contain just as much dangerous weather. Give yourself plenty of room to go around these storm fronts. You also need to make sure you know which direction the storms move. It doesn’t make any sense to divert into an area where the thunderstorms are moving.

Enough of that, let’s keep going.

Our SIGMET, in comparison, barely met the 40% criteria which meant we had plenty of room to divert. Check it out and compare it to the ones above.

So, I discussed with my co-pilot what we could do if we ran into some new developing thunderstorms. The radar picture could change in the next 30 minutes right when we hit the middle of the convective SIGMET. We needed a plan.

We decided we would ask for deviations around the thunderstorms. We specifically decided we would deviate left. We chose left instead of right because the thunderstorms were moving generally north east. We knew this because we used the “play” button on the radar picture.

I always recommend you hit “play” on the radar picture for this very reason. A static radar picture is worthless in my opinion. Add the movement and you suddenly have a ton of information to help you decide which way to go.

We also decided we would ask for a higher altitude once we got up to altitude and took a look.

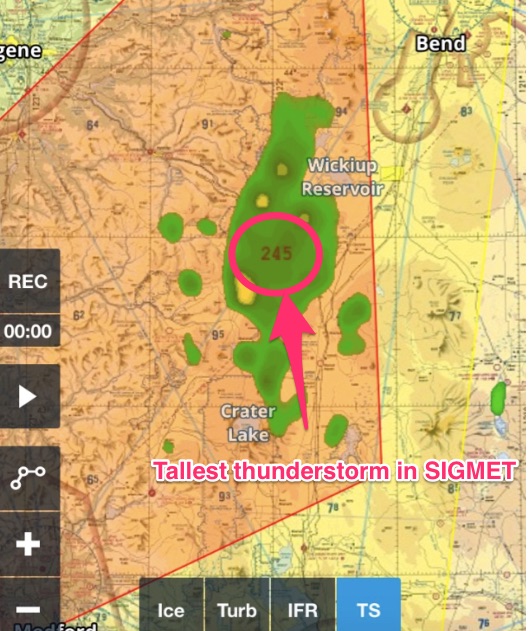

Why a higher altitude than the one we filed? Look at the tops on this thunderstorm:24,500 feet.

We filed for 20,000 feet. I didn’t want to change our flight plan in the system because sometimes when you make changes so close to takeoff, those details don’t get relayed. It’s much easier just to ask ATC once you get airborne.

Our last concern was the possibility of embedded thunderstorms. Nothing scares me more than embedded thunderstorms at night. Weather radar is great, but it has its limitations. We looked at the satellite imagery and saw, except for the thunderstorms, it was pretty clear:

Which meant we would be able to see and avoid the thunderstorms easily. I find this is often the case with thunderstorms. Besides the large cloud formations it is usually (not always) pretty clear.

With an onboard weather radar, Stratus or a satellite weather download we technically didn’t need clear skies when deciding to go through a convective SIGMET, but it helps a lot.

Teaching tangent: Satellite weather downloads always have a delay. You could use them to deviate around a cloud, but you really have no idea what that cloud looks like right now without an on-board weather radar. Use this technique with extreme caution. I only like to use these systems as a last resort to dodge thunderstorms.

To sum it up this is what we decided:

- Ask ATC for higher once we could judge the tops

- Deviate left around the thunderstorms if needed

- Use our weather radar and onboard satellite weather to supplement what we saw

So, that’s it, with the crew brief out of the way, we took off.

We got up to altitude and sure enough: we asked for higher and we deviated to the left.

Teaching tangent: I highly recommend you always ask for at least 2000 feet when changing altitude. First, you need 2000 feet to comply with the east/west altitude rules. Second, it’s really hard to judge altitudes of clouds in relation to your aircraft. Third, what the heck is 1000 feet going to do for you? Not much. Go big. Ask for 2000 feet minimum.

Here are some pictures of the thunderstorms we dodged. The first picture is the northern end of the large thunderstorm. I waited too long to get a really good picture of the big one. Sorry.

The second picture is of another thunderstorm which developed as we were taking off. It hadn’t registered on the radar imagery when we took off. Thunderstorms build quickly! SIGMETs are no joke.

Notice the lower clouds we were able to get up and over? This is typical of thunderstorm activity which is why I never recommend flying through convective SIGMETs for small airplanes and helicopters. You will get stuck in those lower layers.

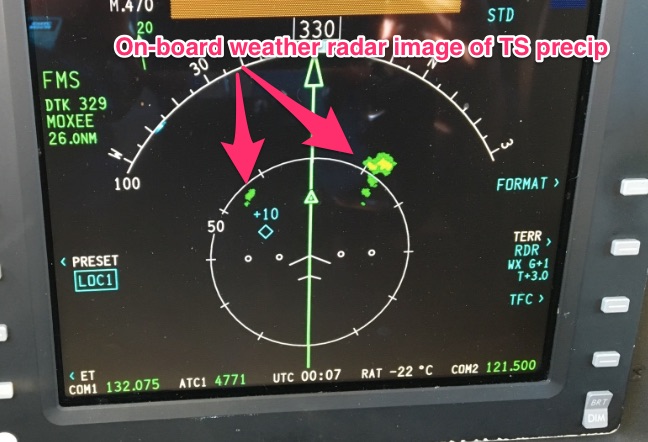

Also, check out this weather radar picture. The blobs correspond to the clouds you see in the pictures above. The larger yellow/green blob is the activity you see in the first picture. The yellow dot eventually turned red. If we had been lower these blobs would have turned red.

I realized looking at the weather radar picture, I still wouldn’t want to be anywhere near the yellow and green parts. If we had just skirted the yellow and green we would have been inside the clouds getting rocked!

Remember, the worst ice is at the tops of the clouds usually. It’s also really bumpy at the tops. On-board weather radars are great, but you have to give those red and yellow blobs a large berth to stay out of the unpleasant bumps and ice.

After we passed the thunderstorms the flight into PDX was uneventful.

I did note that the controller was very generous on our deviation. He told us to deviate left and let him know when we were back on course. I suspect you probably won’t hear that on the East Coast. We have lots of sky and not as many planes on the West Coast.

Lessons learned and review

I successfully negotiated a convective SIGMET, but this was a very unusual case! Here are some reasons you wouldn’t want to do what I did:

Equipment:

- I have on-board weather radar and access to real time satellite imagery. This helps me make accurate decisions if I can’t see the thunderstorms due to clouds. I probably wouldn’t have flown into the SIGMET if I hadn’t had these two pieces of equipment.

- I can get in the Flight Levels. This is huge, people!! Notice one of the major ways I mitigated risk was by flying higher? You don’t have this option as a small GA airplane or helicopter. You are going to fly right through the storm. You also won’t be able to see these storms because you will still be in the clouds. We got up and above all of the clouds.

- Here is a rule of thumb: if you can’t get above the majority of thunderstorm in the convective SIGMET then fly around it or stay home. That should eliminate almost all small GA airplanes and helicopters. Just remember, the height of the thunderstorm you see while on the ground will be substantially higher 30 minutes later.

Experience:

- This wasn’t my first rodeo. I’ve flow around convective SIMGETs outlooks a lot. If you have never flown around thunderstorms before, you should modify your flight plan and steer well clear until you can get experience with a seasoned pilot.

Conditions:

- It was daytime. Being able to see thunderstorms is a game changer. I would have had serious issues with my decision at night. Night changes everything.

- The satellite imagery was light everywhere except the thunderstorms which mean I could see and avoid these clouds.

- This wasn’t a line a of thunderstorms. You cannot punch through a line of thunderstorms like the example below. My particular SIGMET was just a few scattered individual clouds. I had very clear deviating options. Look at the picture below. You would be a fool to fly through these SIGMETs.

Circumstances:

- It’s easy to deviate out West. If there is significant airspace between you and your destination it won’t be easy to deviate.

- You should look at your approach path into your destination airport and the winds. If there is a thunderstorm sitting on your approach path, it doesn’t matter its clear and you can deviate. You might have to fly right through a thunderstorm to land and that’s never okay.

- I hope that helps you understand when you might be able to fly through a convective SIGMET. It was an unusual situation. Most of the time you will see this and you won’t want to fly through it:

Additional Reading:

If you want a good refresher on the differences between AIRMETs and SIGMETs. Check out this article covering everything you need to know about AIRMETs and SIGMETs.

Hey! One more thing!

Did you like this case study? I email my readers every week with more articles just like this. The thing is, these articles aren’t on my blog! You can only get them by subscribing.

Still don’t want to join my email list? That’s okay. You can still download a FREE do-it-yourself weather briefing checklist below. You can unsubscribe after you downloaded the checklist. I don’t mind, seriously! I’m here to help!