I ran into a Navy pilot the other day who had never flown an RNAV approach! I was a little shocked as I thought most experienced pilots had flown Area Navigation approaches (RNAV) before.

Apparently not, which is why I will answer the following questions in this article (plus a few more):

- What is the difference between LPV, LNAV/VNAV and LNAV approach minima?

- How do you know if you can fly one vs the other?

- What is WAAS?

- Why are some LNAV/VNAV minimums greater than LNAV minimums?

Before we get started, I want to make sure I am talking to the right audience. You may think you can do RNAV approaches when you can’t.

First, an RNAV approaches are approaches using an IFR certified GPS installed in your aircraft which gets updated every 28 days.

You can avoid updating the database, but it’s a pain because you have to check the lat/long points by hand. If you don’t want to pay to update your database, you can read how to do that by clicking here.

If you don’t have an incorruptible (you can’t modify approaches) GPS installed in your aircraft (ie Garmin 430 or 530), you can’t do GPS approaches. Go find another article to read, this doesn’t apply to you.

Side-note: No! A handheld GPS or your iPad is not approved for GPS/RNAV approaches so don’t even go there. You won’t be able to file an IFR flight plan with the “/G” designation.

I am not saying you can’t use your GPS when flying IFR for situational awareness. I’m just saying you can’t legally file, ask ATC for, or accept an RNAV approach. You have to stick to VOR and ILS approaches only.

Why can’t you use handheld GPSs? Handhelds don’t have adequate backup power, they may drop signal at a key time, but more importantly, they don’t have Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring (RAIM capability) which is an FAA requirement.

Another side-note: you can always do practice emergency RNAV approaches to LNAV minimums if you don’t have an IFR certified installed GPS. When I flew the OH-58 A/C (which was not instrument rated), we would use our GPS to fly practice RNAV approaches to LNAV minimums in case we inadvertently punched in. It was considered an emergency procedure only.

Now that we’ve cleared that up. Let’s assume your aircraft is legally allowed to file a “/G” flight plan. Congrats, you can do RNAV approaches.

Just to clarify, LPV vs LNAV/VNAV vs LNAV are not types of approaches they are minimums within RNAV approaches. I will go back and forth referring to them as approaches vs minimums just because it’s easier from a copy writing perspective. It’s easier to call them approaches instead of the correct terminology: “RNAV approach to LPV minima.”

You will hear me and other pilots talk as if they are separate types of approaches because they kind of are. An RNAV approach to LPV minima is a very advanced approach compared to a RNAV approach to LNAV minima. Think of LPV approaches as ILS approaches and the LNAV approaches as VOR approaches. Completely different, yet still under the umbrella of an RNAV approach.

Enough side-notes! Let’s break down the different types of approach minimums.

LPV vs LNAV vs LNAV/VNAV

LNAV minimums

LNAV approaches are the most basic of RNAV approaches and as such they usually have the highest minimums. They require no special avionics except a IFR certified installed GPS receiver. Simple Cessna 172s with steam gauges and a Garmin 430 could use these approach minimums.

These are the approaches you will hear pilots argue about whether it’s best to “dive and drive”/”step-down” or do a controlled descent until you hit the next waypoint at the exact altitude. Which technique you choose is completely up to you.

Think of LNAV-only approach minima as the equivalent to a Localizer or VOR approach. It’s missing the vertical component just like localizer approaches with no glideslope.

Teaching Tangent: I personally prefer controlled descents on my LNAV approaches. It increases pilot workload to continually level off then descend. However, I do make exceptions. If the visibility is good but there is a low cloud deck I know I can get under, I will “dive and drive” in an attempt to get as low as possible as soon as possible. Be flexible with this technique and know how to do both.

LNAV/VNAV

LNAV/VNAV approaches are for aircraft with vertical navigation capability (hence the “VNAV”). The vertical guidance is internally generated by barometric settings which is why you see alternate instructions in the notes if you don’t have the local altimeter setting or it’s too cold.

A LNAV/VNAV approach is a GPS version of an ILS approach. It will give you a glidepath indication on your attitude display.

You have to check RAIM for these approaches. You can check RAIM before you take off by going to this FAA website. Your IFR GPS will monitor RAIM throughout your flight. I believe (but don’t quote me) most IFR GPS units also have some ability to predict RAIM at your arrival time as well.

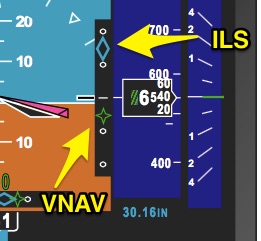

You will know your aircraft has Vertical navigation (VNAV) because you will almost certainly have a more advanced glass attitude display if not a full glass cockpit like a Sandel, Rockwell Collins, a G500, or G1000 etc. I don’t know of any steam gauge with RNAV vertical capability.

Here is a picture of an avionics stack which could display vertical navigation if tied properly into the GPS (Garmin 430, 530 etc). The arrow is pointing to what would display your VNAV information.

Most displays will show VNAV as a “snowflake” instead of a diamond for the ILS approaches. The color of the snowflake will depend on your system. Most of the time they are magenta. This Rockwell Collins Proline 21 system uses green. Check it out.

If you don’t have something like this in your aircraft, stick to LNAV approach minimums.

LPV

LPV approach minimums are for WAAS-equipped aircraft only.

Trust me when I say you will know if your aircraft has WAAS! You will either have bought a brand new aircraft and paid extra for the WAAS, or you sent your aircraft back to the factory to get the WAAS upgrade.

You cannot look at a full glass cockpit and assume it has WAAS. At this point, most full glass cockpit aircraft probably do not have WAAS capability.

For example, the Q400 I flew for the airlines did not have WAAS capability. We were trained on, and could do RNP approaches, but we couldn’t do LPV minimums. It could also do CAT III approaches because of our heads up display, but we couldn’t go to LPV minima. Crazy, I know.

Here’s a pic of the Q400 cockpit to show how you can’t make assumptions.

What is WAAS?

WAAS equipped aircraft have the ability to receive correction signals from the “space segment” of the WAAS system. The “space segment” gets input from the “ground segment.” The ground segment is composed of Wide Area Reference Ground Stations across the US and Hawaii. These stations are precisely surveyed stations.

These ground stations talk to the Wide Area Master Stations which then tell the satellites if they are sending accurate signals. All these pieces talk to each other and constantly update each other. Make sense? Read more here at Wikipedia.

Bottom line: your WAAS system has the ability to constantly correct itself to a more precise location which means you can go to lower minimums! Yay! That’s all you really need to know.

In terms of flying LNAV/VNAV vs LPV, it’s virtually the same. It will look the same on your displays except for one minor detail: you will have some indication on your Pilot Flight Display (PFD) or on the GPS receiver you are ready for “LPV.” It may be in the form of a light on the dashboard, or something will pop up on your PFD. For example the Rockwell Collins Proline21 will say “LPV APPR”.

You will load LPV approached the same. You will fly it the same, and you will push the same “VNAV” autopilot buttons, only now you can go to lower “LPV” minimums.

The LPV minimums are almost always as good as ILS approaches which is why they are becoming so popular. If ATC cooperates with you, you can set up a descent profile well above 10,000 feet, arm the VNAV and drink your coffee all the way to the ground. You don’t have to transition from FMS flying to the ILS and localizer. It’s great.

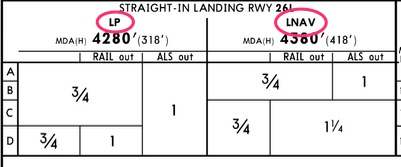

If you don’t see a LPV minimums and only see LP minimums, it’s probably due to terrain or obstacles preventing a lower approach. LPV minima have strict “terping” guidelines. The LP minima are the FAA’s way of saying “sorry we couldn’t get you LPV minima, but we can get you a bit lower than LNAV minima.”

But what about…?

- Why are LNAV/VNAV minimums sometimes higher than LNAV minimums?

- Is an LPV approach considered a precision approach?

- What the heck are LP minimums?

Let’s start with the first: Difference in minimums

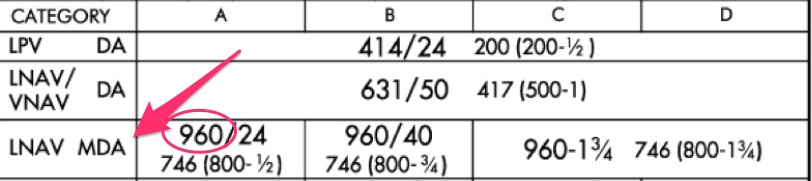

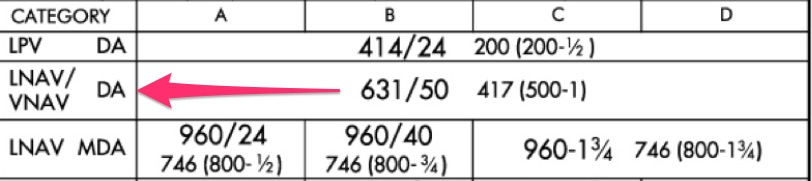

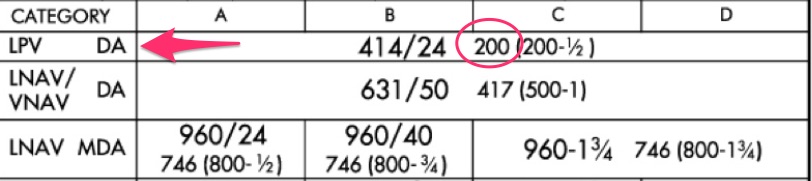

You will always find LPV minimums are the lowest of the three minima, and are often just as good as ILS approaches.

Sometimes, though, the LNAV/VNAV minimums are higher than the LNAV minimums. I really don’t want to go into the nitty gritty of how approaches are built and “terped.” But just know this: approaches with vertical navigation have higher standards for obstacle incursions into the flight path than those that don’t like LNAV minima.

So, if you see LNAV/VNAV minimums that are higher, there is a reason. Something is in the way preventing you from getting down lower while you are on a steady glidepath.

On the LNAV approaches, the hard altitude step downs keep you from those obstacles you might get too close to on a steady glidepath.

Now on to the second: Non-precision vs precision

I heard the FAA considers any approach minimum below 300′ AGL a “precision” approach for check ride purposes. However, LPV approaches are still not considered “precision,” even though the examiner could use it as one of your “precision approaches” on your check-ride.

I have never seen LNAV approach minimums go that low, so it’s always considered “non-precision.”

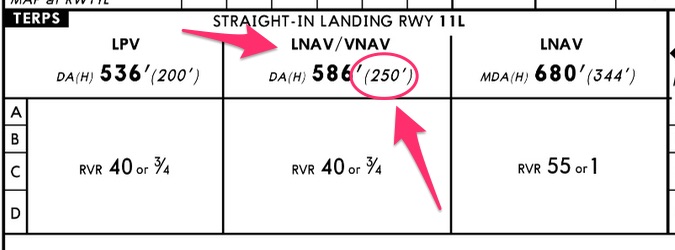

Some LNAV/VNAV approaches flirt with the “precision” minima. But they still aren’t precision. Check out this one:

Also, I want to point out even though some LNAV/VNAV minimums have a “DA” instead of an MDA they still aren’t “precision” approaches! I know your CFI probably told you all “DA” minimums are precision, but you can’t use that blanket statement now that GPS approaches are so prevalent.

The vertical guidance on the LNAV/VNAV is what changes the “MDA” to “DA.” Confused? Yeah, me too.

Third question: LP?

Air Facts Journal published a phenomenal article on LP approaches you can read by clicking here.

Here is an example of an LP approach minimum from a Jeppesen chart:

But if you want the down and dirty, here is a small excerpt to answer your question:

“So what is an LP approach? Actually, it’s just what it sounds like. You probably learned that LPV means “localizer performance with vertical guidance.” Logically, then, LP simply means “localizer performance.” The important point is the lateral guidance is angular, with needle sensitivity increasing as you get closer to the missed approach point (think triangle). By contrast, on a traditional LNAV approach, CDI sensitivity is the same from the final approach fix to the MAP (think rectangle). But unlike an ILS or LPV approach, there is no glideslope on an LP approach. Think of it as the 21st century version of a localizer approach.”

Excerpt written by John Zimmerman on the Air Facts Journal website

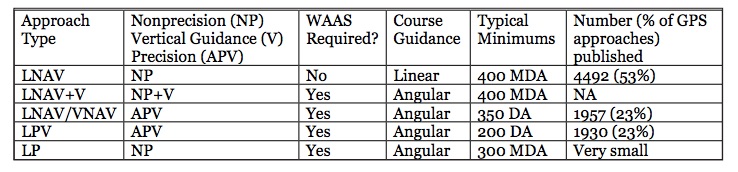

Here is a chart of the different RNAV approaches courtesy of the IFR Refresher magazine (which I love and you should subscribe to!).

Thanks for sticking with me on this long article. If you want to dig a big deeper, check out these articles below:

Additional Reading:

IFR Refresher magazine article: “GPS Approaches Dissected” This article explores LNAV+V approaches which I did not address in my article. This is a must read article.

Max Prescott’s Flying GPS handbook (book link to Amazon)

Hey! One more thing!

Did you like this article? I email my readers every week with more articles just like this. The thing is these articles aren’t on my blog! You can only get them by subscribing.

Still don’t want to join my email list? That’s okay. You can still download a FREE Ultimate Guide to Decoding NOTAMs below. You can unsubscribe after you downloaded the guide. I don’t mind, seriously.

I’m here to help!