It is hard to figure the difference between a category, type, and class of aircraft when pilots first start out.

Part of the problem for pilots is often these definitions don’t apply to them initially. It’s only much farther into your career when you get exposed to different kinds of aircraft that it starts to make sense.

However, this article will lay it out so even if you never fly anything other than a small Cessna, you will still understand the basics. When possible I will include examples and point out some odd exceptions.

First, let’s start with some definitions.

What is a “category” of aircraft?

A category is an overarching classification of aircraft. The following are an example of aircraft categories:

- Airplane

- Rotorcraft

- Powered lift

- The Marine Corp’s V-22 is the best example. The US Army plans to transition its entire fleet of helicopters into this category.

- Glider

- Lighter than air (balloons and airships)

- Powered parachute (not to be confused with powered paragliders)

- Weight-shift control aircraft (hang gliders and ultralight trikes)

What is a “class” of aircraft?

Some categories are further broken down into a “class.” Classes are a way to further distinguish between types of aircraft. Not every category has a class.

The classes most pilots will deal with are “land,” “sea,” “single-engine,” and “multi-engine.”

- Airplane category:

- single-engine land class

- multi-engine land class

- single-engine sea class

- multi-engine sea class

- Rotorcraft category:

- helicopter class

- gyroplane class

- Lighter than air category:

- Powered parachute category:

- powered parachute land class

- powered parachute sea class

- Weight-shift-control category:

- weight-shift-control aircraft land class

- weight-shift-control aircraft sea class

Some of the classifications can get quite interesting! I’ve never seen a multi-engine sea airplane in action, but I’d love to! Here’s a classic example of the Grumman Goose:

So, let’s put the category and classes together with four examples:

- A King Air is in the category of “airplane,” and the class of “multi-engine, land.”

- A UH-60 Blackhawk is in the category of “rotorcraft,” and the class of “helicopter.” Helicopters do not differentiate between multi-engine or single-engine.

- A Cessna 182 is in the category of “airplane,” and the class of “single-engine, land.”

- A Cessna Caravan on floats is in the category of “airplane,” and the class of “single-engine, sea.”

What is a type rating for an aircraft?

The type rating is a designation assigned to certain aircraft so that pilots get additional training before flying them. The FAA decides these aircraft are so complicated they require training above and beyond initial pilot training.

This is where things get confusing.

Here are three overarching rules pilots should know when it comes to type ratings:

- All turbojets, regardless of weight, require a “type” rating.

- Non-turbojet (ie. turboprop) airplanes don’t have a separate “type” rating until they get above 12,500 pounds.

- Most helicopters don’t have type ratings because they don’t weigh more than 12,500 pounds.

For example, most King Air 200s weigh less than 12,500 lbs, so it stays in the airplane category with a class of multi-engine land and no type rating.

The King Air 350, though, weighs more than 12,500 lbs. In order to fly it, you have to get special training and a check ride.

Type ratings go on a pilot’s FAA license. Often times the name of the aircraft and the designated type are completely different (see below).

The FAA outlines its training requirements for a type rating in their Advisory Circular: AC 61-89e.

Type ratings are no joke which is why they are coveted by pilots.

How to find the type rating designation for an aircraft:

It’s difficult to know what the official type rating is compared to the commercial name of the aircraft.

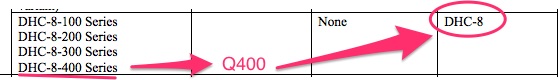

I used to fly the Bombardier Q400 for a regional airline. After I did my final check ride in the simulator, I got a DHC-8 “type” rating. I thought the type rating would read “Q400,” but not so.

Here’s how the FAA lists the Bombardier Q400.

Click here to get the FAA’s list of type ratings to figure out what the different aircraft will translate to on your FAA license.

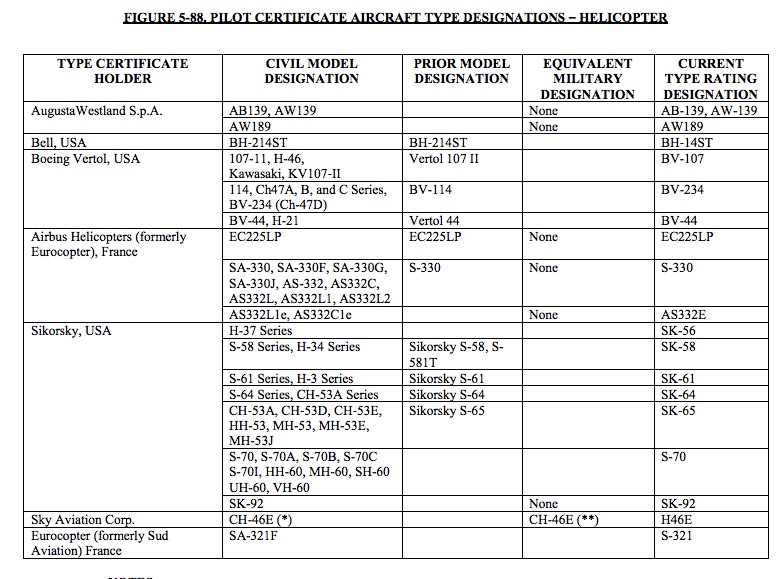

Helicopters generally don’t have type ratings because they usually don’t weigh more than 12,500 pounds. Click here to get the list of FAA type ratings and scroll to the bottom for helicopters.

Here is a screenshot of the helicopters with type ratings.

Notice the UH-60 Blackhawk will go on the FAA license as an “S-70” type.

What is the difference between a type Rating and special training?

Pilots can sometimes confuse “type” ratings with “special training.”

For example, pilots often think you need a “type” rating to fly an R-22 helicopter, but that’s not true. The FAA requires you to have “special training” to fly the R-22 or R-44. You can read more about the SFAR 73-2 by clicking here.

NOTE: “type” ratings mean different things in the international community. Europe and Australia almost always require you to get checked out in every aircraft you fly.

Do you need a type rating to act as a second in command (SIC)?

Please be careful before you go around saying you need a “type” rating to fly a certain aircraft. A lot of time this isn’t true. Here are some interesting exceptions.

Sometimes you only need a type rating to act as the pilot in command (PIC) not the second in command (SIC). In this case, PIC does not mean the “sole manipulator of the controls,” it means to act as the “Captain.” The second-in-command, however, only needs a category rating.

Often times commercial Part 135, 91, or 121 operators will operate an aircraft (like the King Air 350) that requires a type rating, but they don’t want to pay for the type rating for both pilots.

A type rating for a King Air 350 is upwards of $10,000. Instead, they will have a SIC occupy the other seat to help the PIC. The SIC will not fly without the PIC.

So, the SIC might saunter around proudly telling everyone he flies the King Air 350, which is true, but he doesn’t have the actual type rating.

Sometimes the insurance company requires a check ride and additional training. The add on training is not an FAA requirement. The FAA has surprisingly very few training requirements which is why insurance companies will often require a higher standard.

In addition to insurance companies requiring more training, sometimes the customer who owns an aircraft wants both pilots to have airline transport pilot licenses instead of just a standard commercial license.

I bring up these examples to show you that sometimes it is not a regulation driving the additional training, but the client, the insurance company, or the aviation business.

Hey! One more thing!

Do you struggle to understand and decode NOTAMs, METARs and TAFs? Check out the PDF below to get help!