Briefing the instrument approach is an absolute must for every instrument flight for several reasons.

Briefing prior to an approach gives you a chance to catch mistakes you made setting up your avionics, but more importantly, it gets you in the right mindset for the approach.

There is a wealth of information on the approach plate. When you learn how to brief correctly you’ll never miss a thing.

The approach plate briefing is also required for examinations, Part 121, 135, and military operators. However, even if you are a Part 91 pilot, you should still adopt the brief because it will keep you safe and out of trouble.

Okay, so now we know “why” let’s get into the “how.” Here are some techniques I recommend.

Always load the avionics before you brief: The brief is an opportunity to double-check your work. Follow the approach plate to set up avionics. It has all of the info you need to enter the approach into your systems.

Brief the approach in cruise: This substantially reduces your workload as you start your descent.

Brief the approach by following the approach plate: Follow the approach plate using the same flow every time.

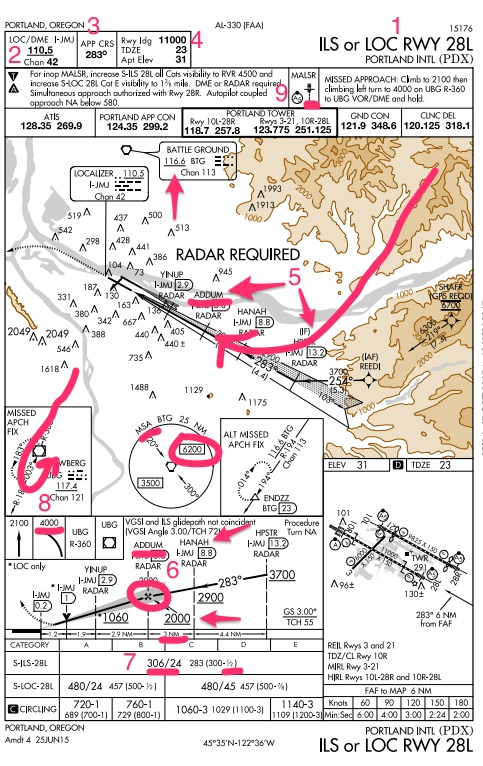

Check out this graphic of an FAA chart below. I numbered it according to what order you should brief. However, do what feels best for you, or is required by your company.

For those of you who use Jeppesen chart, read the entire article anyway!

The only difference is the order of the brief which I show at the end of the article.

How to brief the approach by the numbers.

1. State the approach and runway

I can’t tell you how many times my co-pilot and I have been on different approach charts.

You need to vocalize the procedure and runway to confirm you have the right approach plate and it jives with ATIS and/or the approach ATC told you to expect.

Some Part 121 and 135 operators require you to brief the approach plate # and date.

You don’t want to use an outdated chart or a chart different from your co-pilot. However, with electronic iPads in the cockpit now, this is unnecessary and annoying.

2. State the Localizer frequency…and double-check it!

This is when you double check you have the right localizer frequency entered into your radios!

I can’t emphasize this enough. The point of the brief is not to say things out loud and sound like you know what you’re talking about, it’s so you can check your work!

3. State the approach course…and double-check it!

Double-check you have the right approach course in your avionics.

4. State the runway length and airport elevation

Okay, so you don’t need to actually say the runway length outloud or the elevation (unless your company requires it). I added this because these numbers are important for several reasons.

Short runways should give you pause.

Are you going to have to put the aircraft down immediately and get on the breaks? Do you have to do any performance calculations? For example, at Alaska Airlines, when a runway is less than 7,000 feet, we have to do some landing calculations for the touchdown point.

High elevations should also give you pause.

If the airport’s elevation is higher than 2,000′ you should think about performance. The aircraft may climb poorly during a missed approach.

Use this point to calculate the traffic pattern altitude if you anticipate a visual approach.

Add a 1000′ if you are a helicopter or small airplane. Add 1500′ if you are a large multi-engine aircraft for noise abatement.

For more advanced aircraft with heads up displays, state the touchdown zone elevation as well. The TDZE elevation will need to go into the heads up display system (HGS).

5. Brief the plan view

The plan view is an opportunity to review the overall plan.

Double check you have the VOR and/or ADF frequency in your avionics.

Make a note of the FAF. You need to know the name of the FAF and it’s position relative to other points. For aircraft with glass cockpits you need to quickly pick it out on the screen.

Note your flight path in relation to the approach.

I drew an ugly squiggly line to indicate you should think about how you will intercept the approach path. You don’t have to brief it, but at the very least make a note of your position relative to the approach course.

This will get you ahead of the aircraft by anticipating how ATC will vector you onto the approach.

Note the glide path angle. Is it more than 3 degrees? Because this could result in some higher than normal descent rates. Brief it if it is anything other than 3 degrees.

Steeper approaches require better power management and planning.

Note the Minimum Safe Altitude. Again, you don’t have to say this out loud unless you are in a poor radar environment. It’s hardly ever appropriate to brief this number going into a Class C or B airport.

These come into play more when the controller clears you for the approach early and the altitude is your discretion. You’ll be tempted to put in the altitude at the FAF before clearing the terrain.

This doesn’t happen often, but if you fly in Alaska or out West in mountainous terrain where the controller loses contact, brief this number!

6. Brief the profile view

The profile view has many important elements.

State the FAF’s name so both pilots know what waypoint to look for on the display.

Brief the FAF’s altitude. The FAF’s altitude information is vital to understand if ATC is dropping you above or below the glide path. You do NOT want to chase the glide path.

Knowing the FAF altitude will help you plan your descent and adjust as necessary.

Make a mental note the point 3-5 NM from the FAF to help you gauge when to configure the aircraft.

In this case, HANAH is 3 NM from the FAF. You don’t have to brief this out loud, but the point of the brief is to get you mentally prepared for the approach.

Knowing when you are going to configure is an important part of the brief.

Also, make a note of how far the FAF is from the runway threshold.

Some FAF’s are 10NM out. You will want to wait to configure the aircraft. If the FAF is far out, include that information in the brief, otherwise, don’t say anything.

7. State the decision height (DH) or minimum descent altitude (MDA) and controlling RVR/Visibility

Double check the DH/MDA is in your avionics.

Make a note of the height above ground at minimums. You don’t need to brief it, but take a moment and think about the cloud height in relation to the DH/MDA.

If the DH is 200′ and the clouds are 600′ then you will have 400′ to play with once you break out of the clouds.

Visibility: Remember, you cannot land if the visibility is less than required for the approach. Visibility, not ceiling, is controlling.

For example, most ILS’s require a 1/2 mile visibility. For a 1/2 mile vis, you should be able to see from the beginning of the approach lights to the end of the runway aiming point markings.

Anything less than that you will probably go missed.

Note: this will depend on the type of runway lighting systems and runway markings. Most are about 1/2 mile from the runway threshold and therefore a great way to gauge whether you will have to go around.

I threw this example out there to get you thinking. Click here for an awesome article for runway lighting distances)

8. Brief the missed approach procedure (MAP).

At a minimum state the MAP altitude (4000’).

You will need to dial in the missed approach altitude into the altitude alerter after you capture the glide path, so make sure you memorize the altitude.

Use the visual depiction to brief the MAP or go to the top of the chart and read the written instructions. Your choice.

I also added another squiggly arrow to indicate you should think about what type of holding entry you will use.

In this case, it is a parallel entry. If you always brief it, you will quickly become an expert on identifying holding pattern entries.

For visual approaches, you don’t need to brief the missed completely, but at least tell the other pilot you aren’t going to brief it.

However, you should still look at it because if you have to do a go-around for some other reason, you need to know where you’re going.

Do you fly with a Flight Management System (FMS)? Double check the MAP is in the box.

9. Runway Lighting and Notes

You don’t have to include the runway lighting in the brief, but you should make a note of the runway lighting and if it’s working.

You need to know what you’ll see when you break out at minimums. You may also need to raise visibility requirements if it isn’t working (see the operator notes on the 28L approach chart above).

Only brief the notes if they are applicable. Most of the time they aren’t, but you need to always look at them anyway.

For example, if the MALSR lights are working you don’t need to brief what you need to do if they aren’t working.

BONUS #1: Brief the Exit Plan and Taxi Plan and NOTAMs

Always brief your exit strategy off the runway. Know where you need to go before you need to go there!

I urge you to always brief the expected exit off the runway and taxi plan and gate number. I’m speaking from experience. I’m trying to save you from mass confusion on the ground.

This is when you highlight any runway or taxiway NOTAMs which may prevent you from taxiing on your normal route.

BONUS #2: Double check the radio frequencies

Don’t brief the frquencies, but like the Localizer frequency and approach course, you should check you have as many frequencies entered as you can.

If you are an airline pilot, this is when you put company’s freq in the box and/or switch off of monitoring Guard (121.5).

You don’t need to monitor Guard during the approach sequence. Leave that up to the pilots in cruise to help, you are about to enter a critical flight profile.

Also, this is when you make a note of the ground frequency. It isn’t always 121.9.

If you’re a future first officer, get in the habit of writing down all the different ground and ramp frequencies. Again, don’t brief it out loud, but take this opportunity to prepare!

BONUS #3: Brief alternates and fuel required

When the weather gets really bad, take this opportunity to do some advanced planning.

How many approaches can you do before you have to go to your alternate? Sometimes you’ll have a ton of fuel and can go missed several times, other days, you only get one shot.

Whatever the situation, brief it in cruise!

Note: you should know how much fuel it takes your aircraft to do one missed approach and full approach. For example, we plan about 6000 pounds of fuel in the 737 for one approach.

Example Brief:

Based on the above example this is what a full brief might sound like:

“All right, we are doing the ILS 28L into Portland, the localizer frequency is 110.5 which is the box. The approach course is 283 which is dialed in.

We have 11,000 feet of runway and airport elevation is 23 feet. We are approaching from the north so I expect a right turn onto the approach course.

The FAF is ADDUM at 2000.’ I will configure the aircraft around HANAH. We need 2400 RVR to do the approach which we have.

The missed approach procedure is to fly straight ahead to 2100′ and then do a climbing left turn to 4000′ on the Newburg 360 radial to Newburg where we will hold. We will do a parallel entry into holding.

Radar is required for this approach. The autopilot has to come off by 580 feet. After landing we will turn right on taxiway B3 and gate C1. Any questions?“

Here is what a bare-bones brief might sound like:

“All right, we are doing the ILS 28L into Portland, the localizer frequency is 110.5 which is the box.

The approach course is 283 which is dialed in. We have 11,000 feet of runway and airport elevation is 23 feet.

The FAF is ADDUM at 2000.’ We need 2400 RVR to do the approach which we have.

The missed approach procedure is to fly straight ahead to 2100′ and then do a climbing left turn to 4000′ on the Newburg 360 radial to Newburg where we will hold.

After landing we will turn right on taxiway B3 and gate C1. Any questions?“

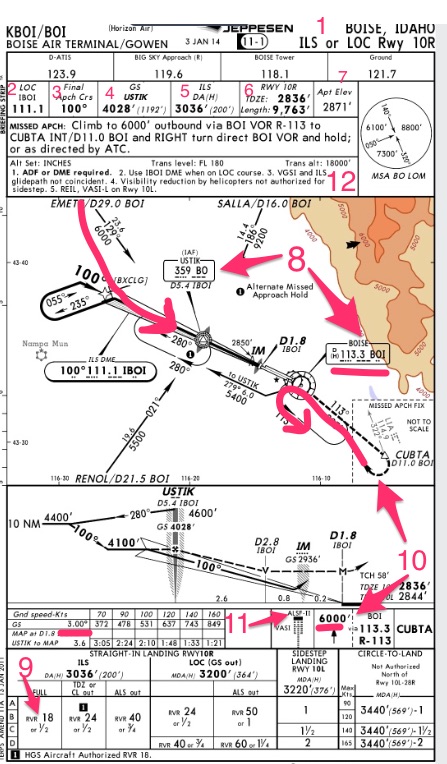

JEPPESEN Approach Chart Brief

The meat of the brief remains the same, but the order in which you brief it changes with Jeppesen charts. The Jepp charts make it easier to brief.

My numbers are not the same as the numbers on the FAA chart, but I think you are smart enough to figure out the difference.

So, that’s it. That’s how I like to brief approaches.

Everyone uses a little bit different of a technique. Develop your own through practice.

There is a wealth of information in the approach plate.

The plate is a reminder for a myriad of little things that will ruin your day (i.e. runway length). It is also an opportunity to get ahead of the aircraft and anticipate ATC’s next move.

You should always brief the approach even if you are flying alone.

Plan ahead and do it in cruise flight when the cockpit isn’t as busy. When you fly into unfamiliar airports, spend a little more time digesting all the information.

Hey! One more thing!

Have you been struggling with NOTAMs? Check out this FREE Ultimate Guide to Decoding NOTAMs PDF below.

You can unsubscribe after you downloaded the guide. I don’t mind, seriously.

But, you might want to stick around because I send out emails with helpful flying tips and resources.

I’m here to help!