Pilot reports of weather (PIREPs) are an excellent way to understand what’s actually happening with the weather.

However, they are difficult to read.

Do you find yourself skipping over them because you can’t remember how to read them? You’re not alone.

This article will explain how to read PIREPs and a whole lot more. Thankfully, with just a little bit of effort, you can quickly learn to read PIREPs.

PIREPs are full of important and useful information.

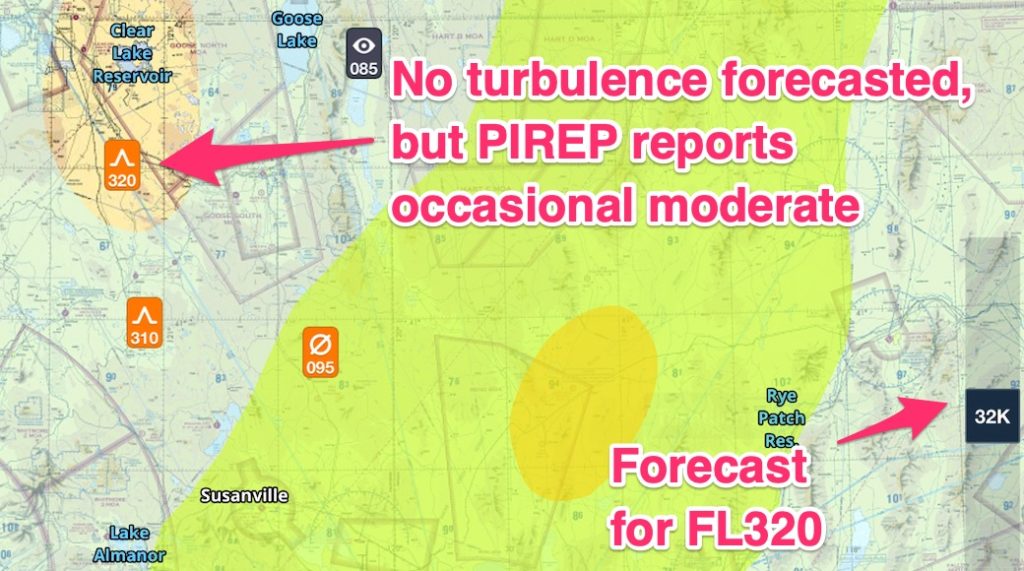

Here is a perfect example of why PIREPs should be an important part of your preflight:

The forecast predicted moderate turbulence but not where it manifested. In the image above, the darker the yellow, the more intense the turbulence. (This is a function of Foreflight which, if you don’t have, you need to get!)

Do you see why PIREPs are important? They tell you what’s actually happening.

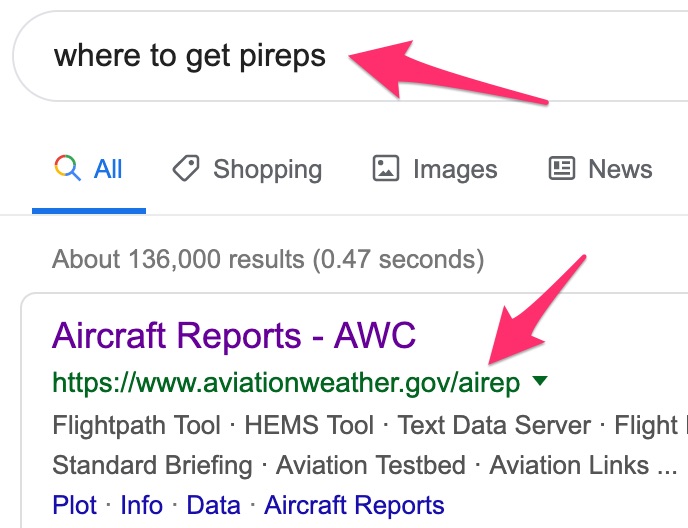

Where do I find PIREPs?

The most common place is the National Weather Services’ website. Google “where to get pireps,” or just type “pireps” and this website should come up:

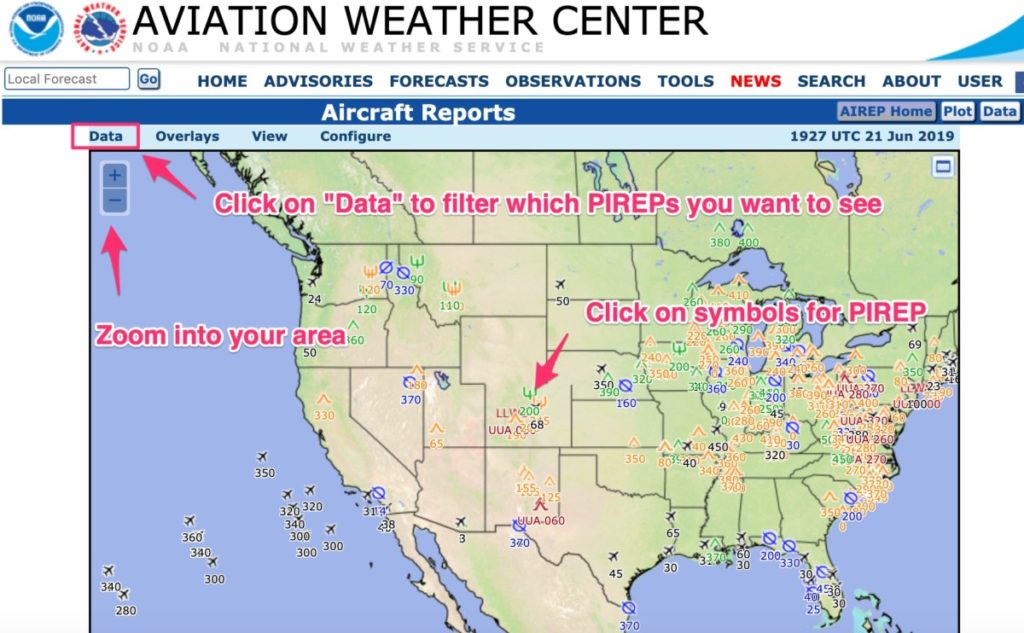

The website looks like this:

You can click and hold down on your mouse button to move the map around. Use the zoom buttons to get close to your area.

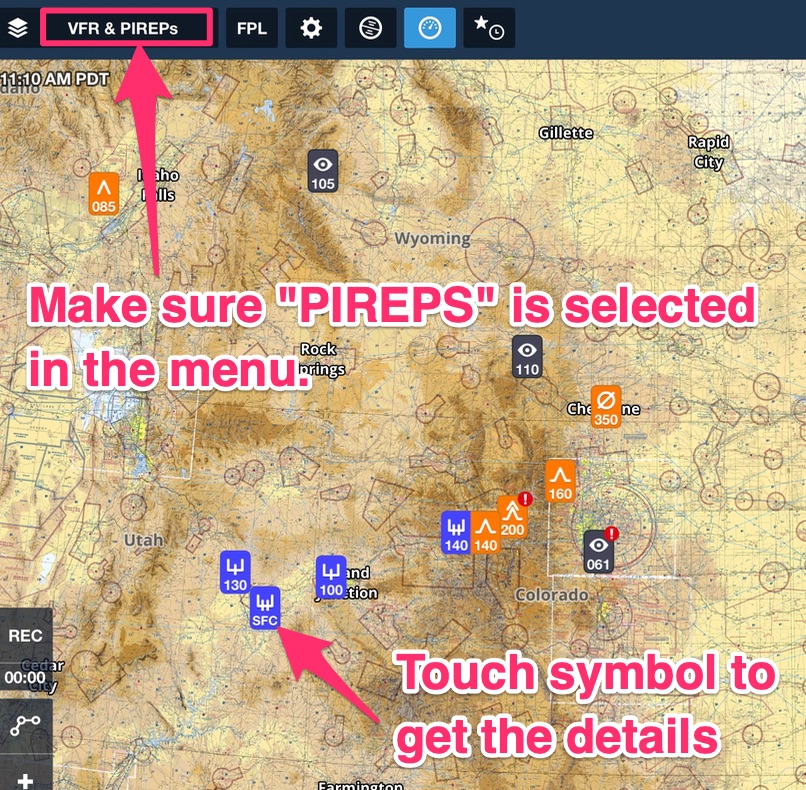

If you don’t want to use the free website, check out Foreflight. Or use any generic weather app.

Because they are so important, you will find them on any standard aviation weather application.

Here is an example of Foreflight:

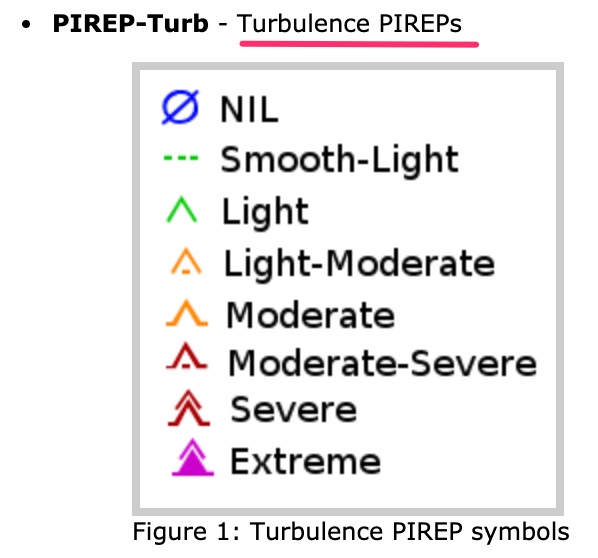

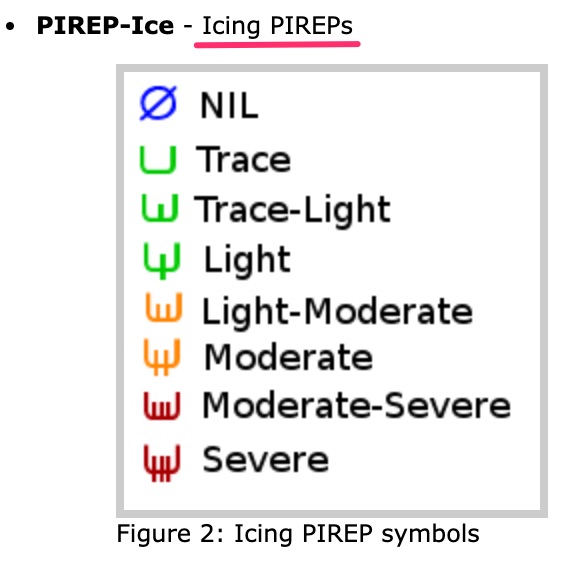

What do the PIREP symbols mean?

Okay, now you know where to get them, but how do you read them?

Let’s start with the symbols.

You should be familiar with the symbols displayed on the PIREP map.

How to read PIREPs

Now you know what the basic symbols look like and where to find PIREPs, next you need to know how to decode PIREPs.

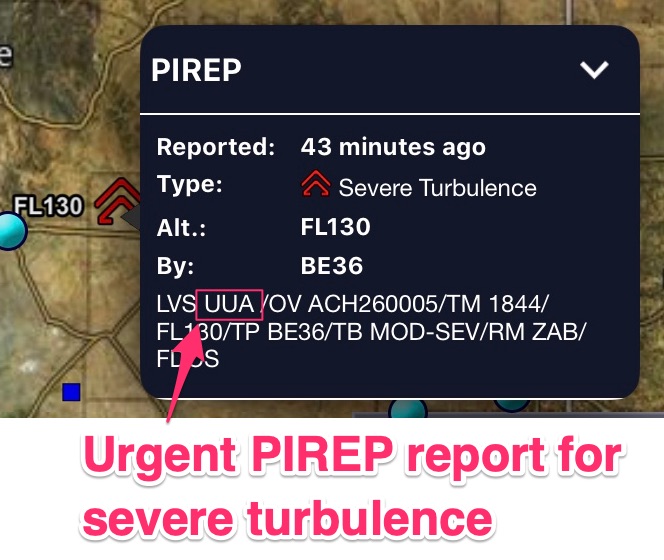

There are two types of PIREPs: UA and UUA.

UA: Routine (or anything not classified as “Urgent”)

UUA: Urgent. Urgent includes the following:

- Tornados, funnel clouds or waterspouts

- Severe or extreme turbulence (including clear air turbulence)

- Severe icing

- Hail

- Low-Level Windshear (LLWS) which is defined as fluctuations of more than 10 kts of airspeed

- Volcanic ash clouds

- Any other weather that the weather specialist may deem hazardous or potentially hazardous to flying.

As you can see, Urgent PIREPs are serious. Anytime you see a “UUA” or “Urgent” on a PIREP, it’s time to stop and think: “what am I gonna do about this UUA PIREP?”

It may be you don’t fly, or you modify your flight plan considerably.

Remember, these PIREPs represent actual conditions and therefore you should take any “Urgent/UUA” PIREP very seriously.

How to decode PIREPs

PIREPs are broken down into eleven lines. Not all of the lines will show up on each PIREP.

The next eleven potential lines in PIREPs are as follows:

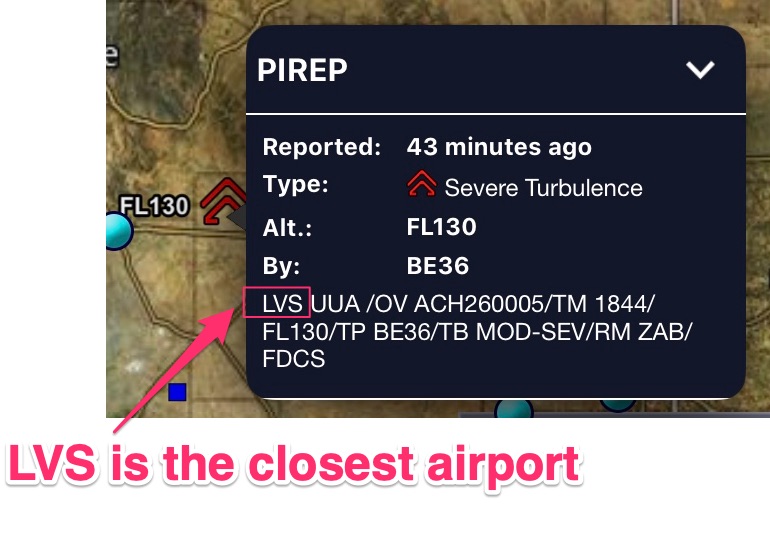

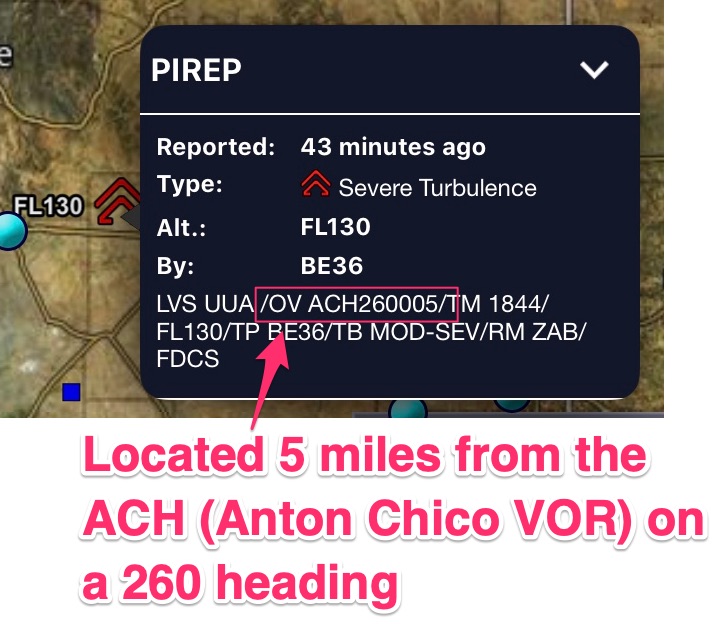

/OV: these are 3-letter NAVAID/Airport idents only.

The three letters after “OV” is a NAVAID or Airport and not some random acronym you forgot. You don’t have to rack your brain to try and remember what “RFD” means.

It doesn’t mean anything, it’s a VOR or NDB or airport (but probably a VOR).

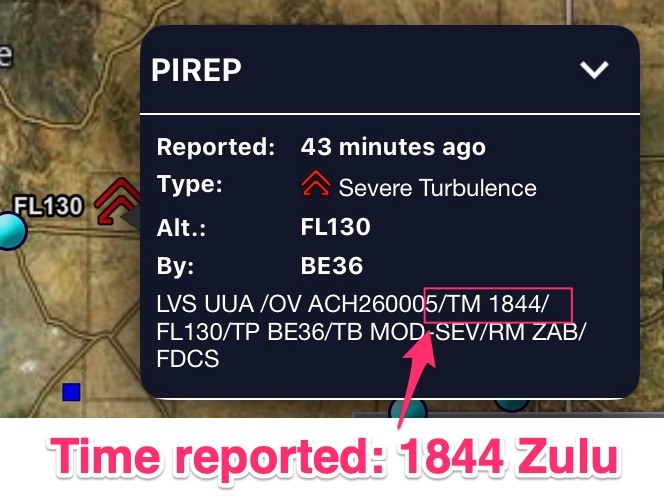

/TM: 4 digit time stamp in ZULU/GMT time.

It’s important to note the times on PIREPs. If it’s more than a few hours old, it might not apply especially if the PIREP is related to a fast-moving thunderstorm.

Don’t know what GMT is right now? This is when your phone comes in handy. Download “Zulu Time” for your iPhone or go to zulutime.net to translate time quickly to Zulu.

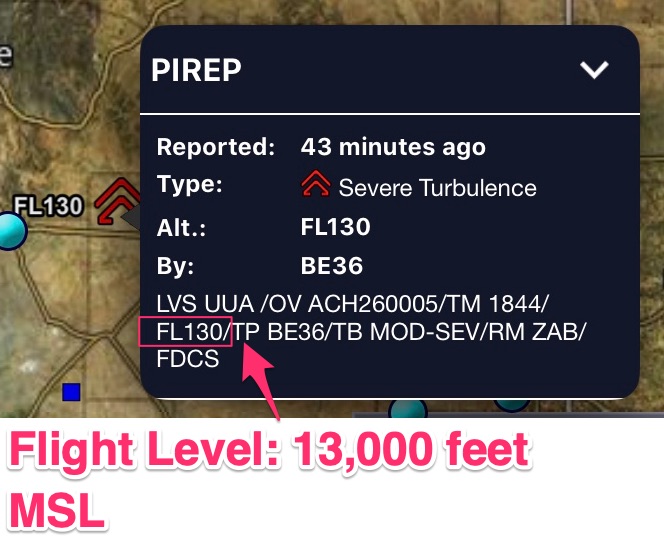

/FL: Flight level. Reported in 3 digits for hundreds of feet.

If the flight level isn’t known then you will see FLUNKN (which kind of looks like “flunking” as in, I flunked my PIREP report by not providing the altitude)!

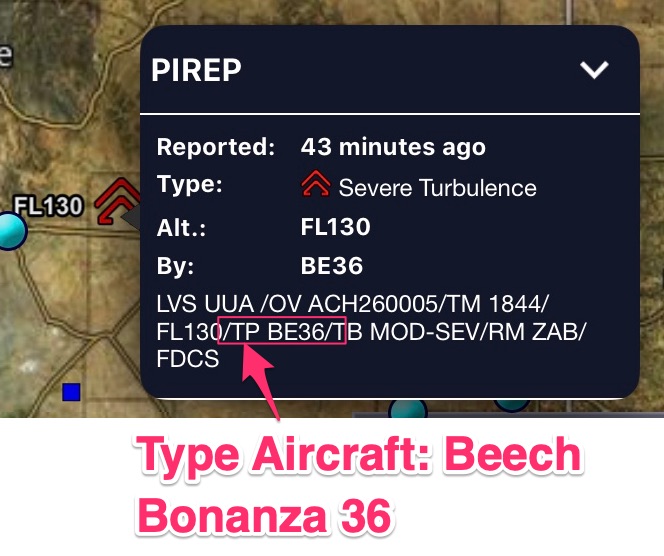

/TP: Type of aircraft.

This one is difficult unless you know your aircraft types.

You may have to use Google to figure it out. Just type the term you see in the PIREP.

For example, I typed: “PC type of aircraft,” “PA type of aircraft,” “B738 type of aircraft” and it should come up with pictures and all!

Here are some common letters and associated aircraft to help you out:

- “B” for Boeing

- Note: the Boeing numbers can be confusing. You’ll see /TP B739 or /TP B738. Boeing doesn’t make 738s or 739s. They make an 800 and 900 model of the 737. So, you’ll see 738 for the 800 or 739 for the 900 models. Treat them both the same.

- “BE” for Beechcraft

- “L” for Lear

- “C” for Cessna

- “PA” for Piper

- “PC” for Pilatus

- “E” for Embraer

- “DH” for Dehavalind (Dash 8 or Q400)

- “A” for Airbus

You will want to pay attention to the types of aircraft because a Boeing 737 reporting “moderate” turbulence could mean “severe” turbulence for a tiny Cessna 172.

/SK: Cloud layers. Cloud layers are described as follows:

- Height to cloud base in hundreds of feet, so 001 is one hundred feet, 030 is 3000 feet and 300 is 30,000 feet (if not known you will see UNKN)

- Cloud cover symbol

- Height of cloud tops in hundreds of feet

- The solidus (/) will separate layers if there are multiple layers

- A space will separate each sub-element.

For example:

- /SK 038 BKN (Clouds are broken at 3800 feet)

- /SK 055 SCT 073/085 BKN 105 (Clouds are scattered at 5500 feet as well as scattered at 7300 feet and 8500 feet. Clouds are broken at 10,500 feet)

- /SK UNKN OVC

/WX: Weather.

Flight visibility is reported first which makes sense because visibility is extremely important.

Note: the intensity is not reported like in METARs where you will see -RA for light rain or +RA for heavy rain.

/TA: Air temperature in Celcius.

If it’s below zero you will see a hyphen. /TA 15 vs a /TA -15 (15 degrees C vs negative 15 degrees C)

/WV: Wind velocity.

The wind direction is first and then the speed just like you will see in METARs.

The difference is the wind is reported in six digits so a 45-knot wind from heading 270 degrees looks like this: /WV 270045

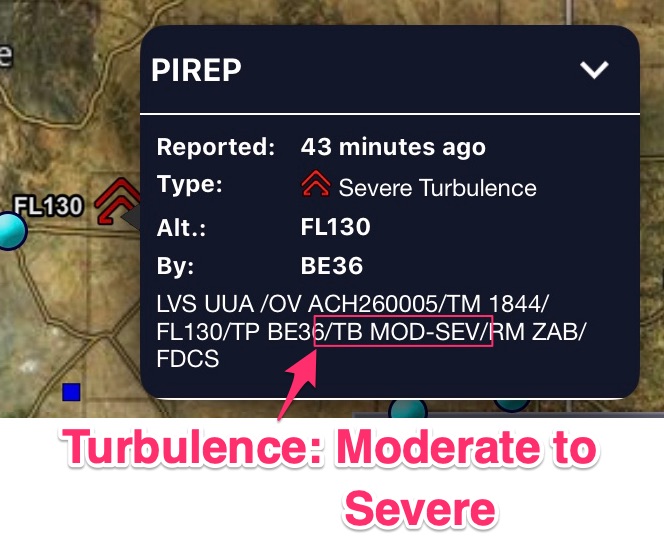

/TB: Turbulence: the standard contractions for intensity are used (EXTRM/ LGT/MOD)

The altitude is reported only if it is different from the altitude reported at the beginning of the PIREP on the “/FL” line.

/IC: Icing is described using standard intensity and type contractions just like turbulence.

The altitude is reported only if it is different from the altitude reported at the beginning of the PIREP on the “/FL” line.

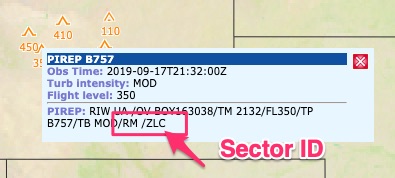

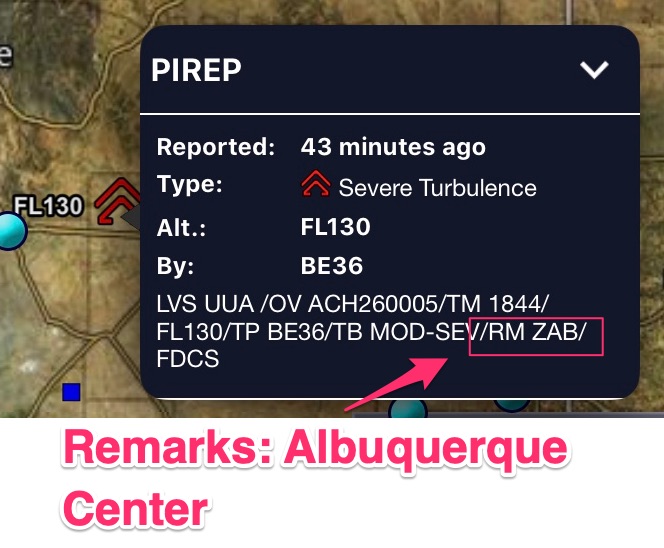

/RM: Remarks. The most hazardous element comes first.

The remark section is used to clarify something in the report.

Occasionally you will see a slash odd three-letter identifier in the Remarks section. This is the sector reporting the PIREP. Check it out:

I’m not sure why they put this in the remarks section. It’s not relevant to you as a pilot because the NAVAID is referenced at the beginning of the PIREP.

Here is another example:

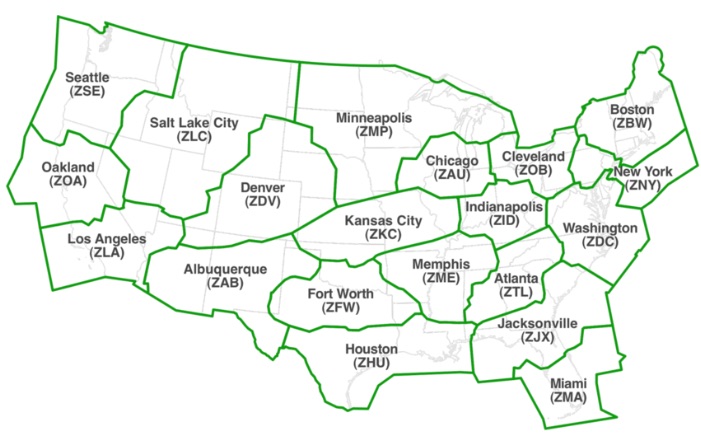

In case you want to know the different air traffic control sectors, check out this map:

It is useful to know that anything in a NOTAM or PIREP beginning with a “Z” is most likely an ATC sector identifier. You will run into these acronyms occasionally.

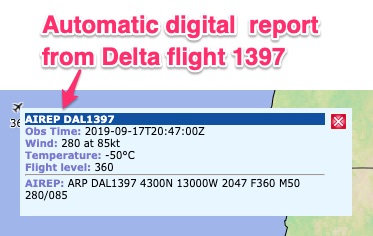

What is the difference between a PIREP and an AIREP?

On the FAA’s AWC PIREP site you will see two different types of PIREPs. One will say “AIREP” and the other “PIREP” at the top. Check it out:

The AIREP is an automatic report sent from the aircraft’s computer to the National Weather Service. The information isn’t as useful as a full PIREP since it usually only includes the winds, temperature and the flight level.

This is an invaluable tool for weather forecasters and pilots, especially for flights over water.

There are no weather stations between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans except for aircraft who send data automatically back to forecasters.

We have access to this data as well! If you ever need to know real-time winds compared to forecast winds over the ocean (Let’s say you are ferrying an aircraft from Alaska to Hawaii), this is where you could see if you’re gonna make it!

How do I make a PIREP?

I encourage all pilots to make the reports, especially on the information you wish you could have prior to taking off.

The most important things to report are:

- Cloud tops

- Ceilings

- Icing* (this report really helps pilots flying aircraft with no anti-ice/deice capability)

- Turbulence

This article is about how to read PIREPs, not give them so, to learn how to make PIREPs check out these articles:

How to Report Turbulence the Right Way

How to File a Pilot Report (PIREP)

How long are PIREPs valid?

I couldn’t find a definitive answer to this question. If you are an aviation weather professional please email me if you know.

In general, PIREPs will generally stay in the system for an hour. After an hour they aren’t usually relevant. For every minute that passes, a PIREP becomes less valid.

As a pilot, please pay attention to the time (/TM) of the PIREP. If it was made an hour ago and it will take you three hours to get to the location of the PIREP, it probably isn’t valid.

What if I run into a PIREP I don’t understand?

This will still happen even if you read this article. So, I have two solutions for you. The first is you can download a PIREP cheat sheet for future reference below.

However, this will only solve part of the problem for you. I have created a more comprehensive PDF which will let you decode PIREPs, NOTAMs, METARs, and TAFs. This document is regularly updated and you can purchase it here.

I keep it on my iPad for reference during pre-flight planning.

Additional Reading:

FAA PIREP Cheat Sheet/Decoder PDF (really useful!!!)

FAA official document governing PIREPs (very in-depth)