For new instrument pilots, the runway visual range (RVR) systems are a little intimidating and confusing. Why use RVR instead of just using the visibility report? What is the difference between visibility and RVR reports?

I will answer all of these questions and more.

The RVR report has important legal implications for instrument pilots.

Let’s start with the basics and then I’ll explore how RVR relates to standard takeoff minimums, lower than standard takeoff minimums and approach weather requirements.

What is the runway visual range (RVR) and why is it important to pilots?

Runway visual range is a measurement of actual visibility down the runway.

Put simply, it is a tool to help pilots evaluate whether they can land or takeoff.

The advantage of the RVR system is it gives you an excellent idea of what’s happening on the runway.

This is an important distinction because visibility reported on the METAR doesn’t give completely accurate visibility readings if the weather station isn’t near the runway.

Have you ever flown out of an airport where the arrival end of the runway is completely socked in but the other three-quarters of the runway is clear? The METAR would report “clear,” if the weather station is on a clear part of the field, but the RVR report would measure the lower, more accurate visibility.

How is RVR reported?

RVR is reported in either feet or meters. In the United States, you can assume it is in feet.

This may seem like a no brainer, but RVR is only reported at airports with an RVR system installed. If you only see visibility reported in statute miles on the METAR, the airport probably doesn’t have RVR.

Note: this isn’t always the case. I took off from Alexandria, Louisiana and the METAR reported visibility in statute miles, but the tower had an RVR readout. Go figure. I don’t know why they didn’t update the METAR with RVR.

You can assume all Class B and Class C airports have RVR, but the Class D airports may not.

How do you know if an airport has RVR?

There are a couple of ways you can find out. The easiest is to go to the FAA’s RVR status monitor page.

Don’t see your airport? Then they probably don’t have RVR. For those of you in the US, I highly recommend you bookmark the RVR monitor page. It is fantastic!

For anyone outside the US, do some research. I suspect there is an equivalent website although I could not find it.

I did a quick screenshot of some (not all) of the airports with RVR:

Note: The background behind KELP is black because the RVR system is out of service. Here is the corresponding NOTAM:

The FAA’s status monitor page is a quick way to determine if the RVR is working at a particular airport.

Just be careful and check the NOTAMs as well. The NOTAM website and the RVR Status Monitor website do NOT talk to each other.

How do you translate RVR to visibility?

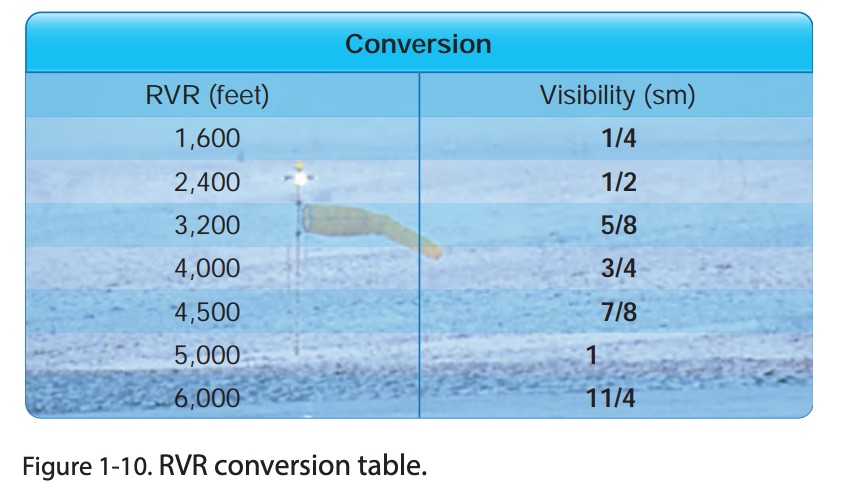

Sometimes you will need to translate the visibility into RVR or vice versa. The CFR 91.175 (h) (2) has a table with corresponding RVR (feet) and Visibility (statute miles).

The FAA also provides a colorful chart in the FAA’s Instrument Procedures Handbook:

What RVR do you need to do an approach?

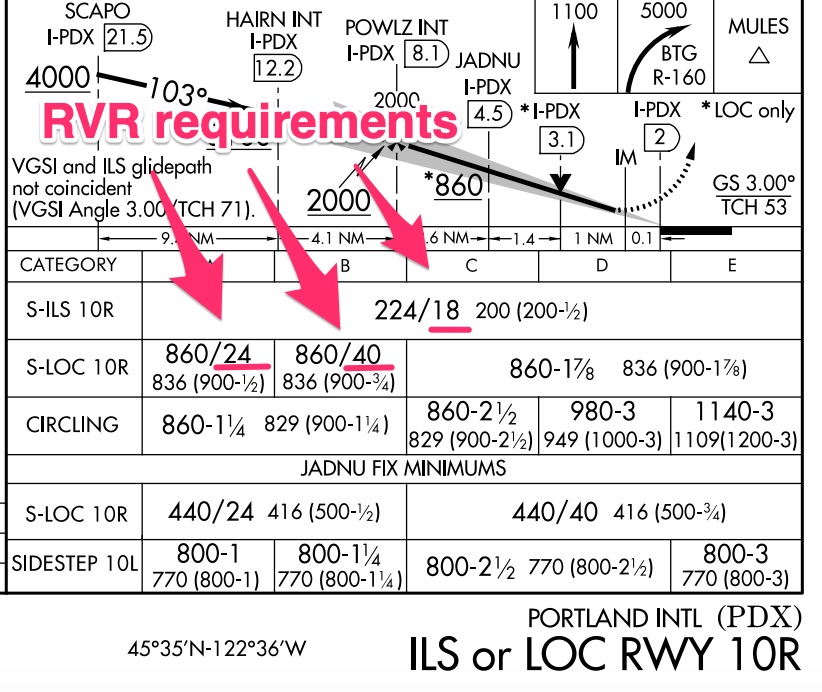

Every approach plate will show you what RVR requirements you need.

In this example, the ILS 10R at Portland requires either 1800 ft of RVR for all categories. The “18” translates to 1800 feet. They shorten it for easier reading.

Note the Category “B” aircraft need 4000 feet of RVR for the “S-LOC” or Localizer approach. The Localizer is like the ILS but it lacks the vertical guidance so the requirements are higher. It’s not as precise.

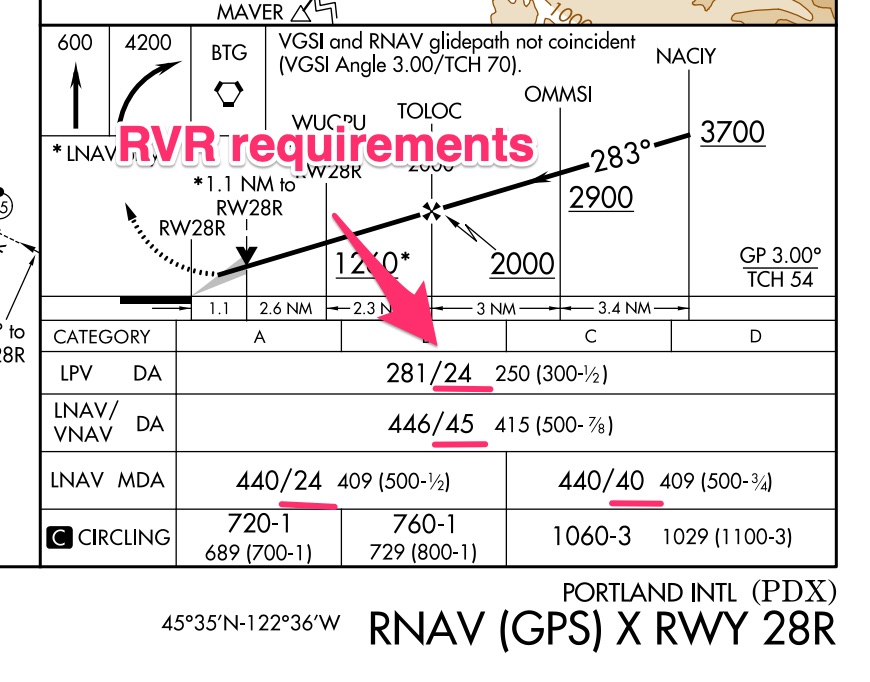

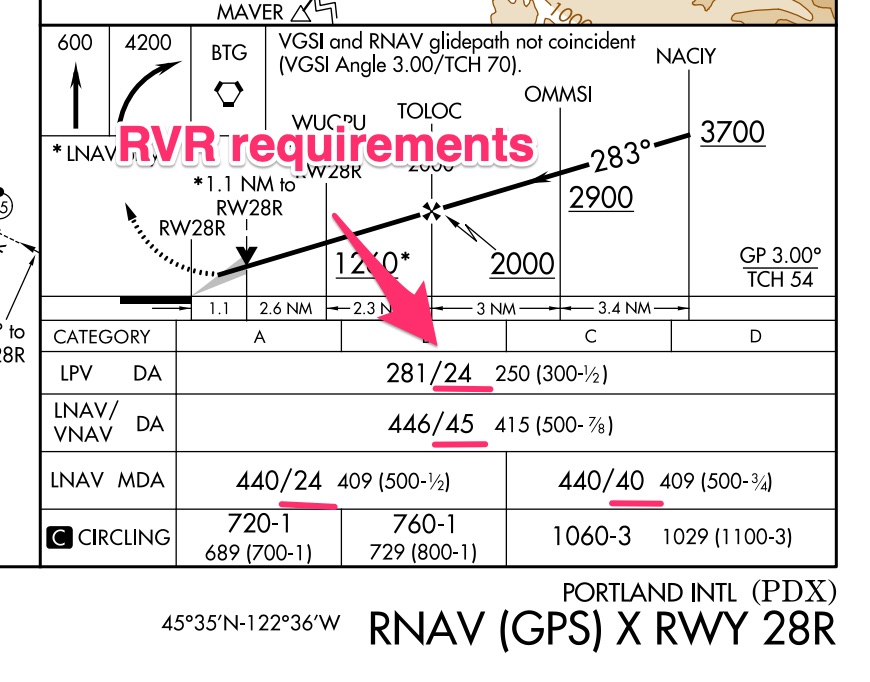

How do you find RVR requirements on FAA charts?

I showed an example above, but here is another example of how to find the RVR requirements for an approach on an FAA chart. If you don’t see a two-digit number then you have to use the visibility report from the ATIS, and not the RVR report (i.e. “1 1/2” vs “24”).

What happens if the RVR is lower than the RVR requirements for the approach?

This is a loaded question. I want to say no one can land, but that’s not entirely true. It depends..do you fly for a Part 121, 135, 91 or military operation?

Note: if you don’t know the difference between the different “parts,” check out this article I wrote: What is the difference between Part 91, 121 and 135?

For Part 121 and Part 135 operations pilots need to consult their Operations Specifications, but in general, you cannot start the approach if the visibility is below minimums.

Some operators can continue if the reported visibility drops after they pass the FAF, but some have to execute the missed past the FAF if the tower gives an update and the RVR drops below minimums. It depends!

How do you know what the approach minimums are for the approach? Simple, I showed you earlier:

Part 91 and military operators, however, can continue past the FAF with an RVR lower than the approach requires, but they still have to have the visibility requirements at the time they land.

All pilots (yes, ALL) must also have to have the runway environment in sight before they can continue below the DA or MDA. There is a long list of the items that qualify as the “runway.” You’ve probably run across this list. Check out the requirements by reading the 14 CFR 91.175.

Remember, it’s not the ceiling, but visibility which determines whether you can land or takeoff which is why RVR is so powerful.

Don’t have the visibility or runway in sight? Too bad. You can’t take off and/or land. You aren’t legally allowed to.

What RVR do you need for lower than standard takeoff minimums?

I have written an extensive article on lower than standard takeoff minimums. RVR is an integral part of operating below the standard. Check out my article to fully

You also need RVR for standard takeoff minimums (1 sm visibility up to two engines, 1/2 sm visibility for three engines or more).

This is where the conversion chart comes in handy. One statute miles equals 5,000 feet of RVR.

I hope that helps. If you have any more specific questions feel free to email me at thinkaviation@gmail.com.